Android App Design

Get familiar with the essential Material Design Guidelines you need to know while building an app for Android

Android's open-source ecosystem presents unique design opportunities and challenges for mobile designers. Material Design, Google's design language, establishes the foundation for creating intuitive and visually cohesive Android applications. The platform's flexibility enables designers to craft experiences across various device types while maintaining consistent interaction patterns and visual hierarchy.

Understanding Android-specific design principles helps create apps that feel native to the platform, from navigation patterns and typography to component behavior and motion design. Material Design's emphasis on physical surfaces, meaningful motion, and adaptive layouts guides designers in creating apps that delight users while maintaining platform consistency. Through thoughtful implementation of Android design patterns, designers can build applications that seamlessly integrate with the operating system's core functionalities and meet users' expectations for fluid, responsive interactions.

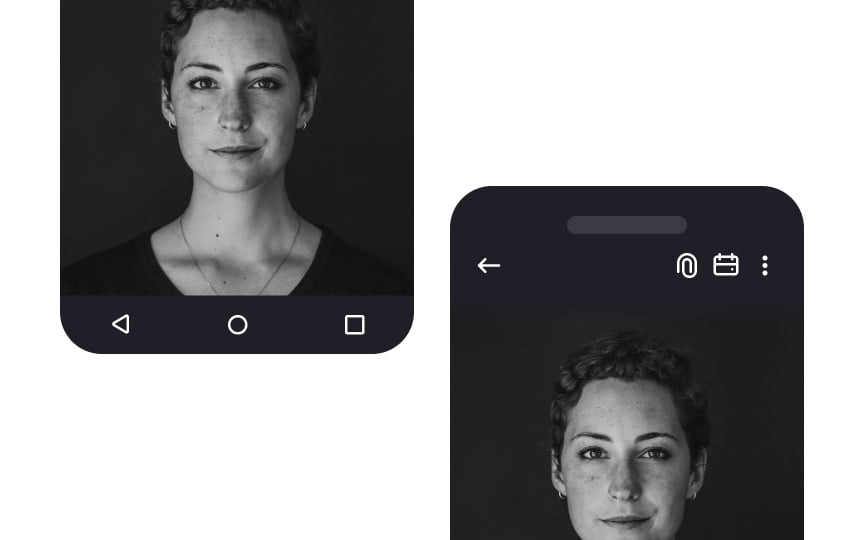

Device manufacturers customize Android's appearance and functionality through custom software overlays, called UI skins. Samsung's One UI, Sony's Xperia UI, and Google's Pixel UI represent distinct interpretations of the Android platform. These manufacturer-specific modifications create unique design considerations for each Android variant.

Designers must account for these different Android implementations when creating applications. Each app's interface should maintain consistency with the underlying system UI while adhering to Material

The

The versatility of Android extends far beyond mobile devices. Smart home systems, automotive interfaces, and entertainment devices leverage Android's adaptable architecture to create specialized experiences. This flexibility enables manufacturers to optimize the operating system for specific use cases, from voice-controlled displays to car infotainment systems.

Connected devices require robust mobile interfaces for control and monitoring. Android's widespread adoption has fostered a rich ecosystem of companion apps that bridge the gap between traditional mobile interfaces and emerging smart device categories. This interconnected environment demands thoughtful design considerations for seamless cross-device experiences.

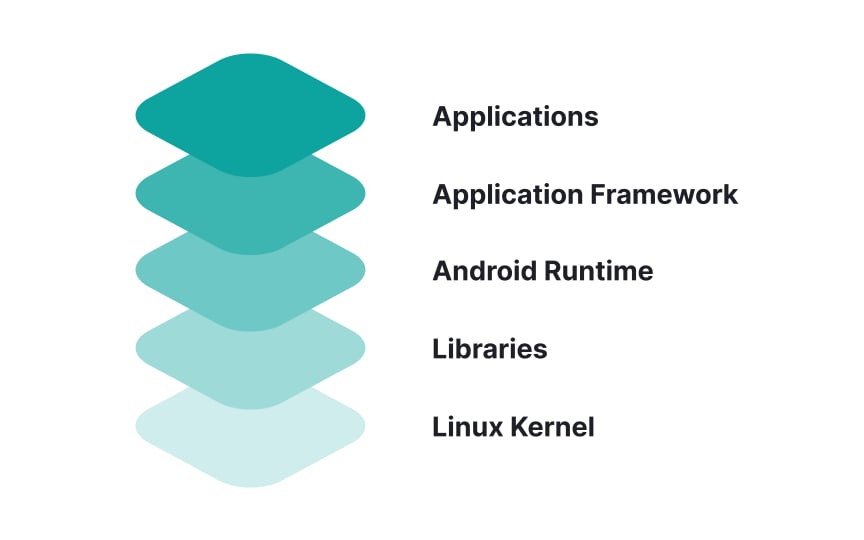

Android architecture, or the Android stack, consists of 5 layers:

- Linux Kernel exists at the root of

Android architecture. The kernel handles device drivers, power, memory, device management, and resource access. - Native Libraries like WebKit, OpenGL, FreeType, and others are on top of the Linux Kernel. They support browsers, fonts, databases, video, and audio.

- Android Runtime provides the base for the application framework and powers applications with the help of the core libraries.

- Application Framework includes Android

UI , telephony, resources, locations, data, and package managers. It provides a lot of classes and interfaces for android application development. - Applications form the top layer of the Android stack. Pre-installed apps like home, contacts, camera, and third-party apps like social networks will be installed on this layer.

Average Android users primarily interact with the Applications layer when using apps (making phone calls, surfing the internet, etc.). The layers further down are usually just accessed by developers.

- Home screen: Android’s Home screen doesn't follow a rigid

layout , so users can arrange app icons in any chosen pattern. They can also add widgets, calendars, different time displays, and other features. - Launcher Apps: Apps like Nova and Niagara allow users to change the look of Android completely. For example, they allow users to add more icons to the dock, have wallpapers that change over time, or use custom

navigation gestures. - Default apps: Users can set a default app for many tasks: messaging, emailing, browsing, typing, and calling.

- Dual messaging: Samsung offers Dual messenger on their dual-SIM Android phones. It lets you use two different accounts with one chatting app like WhatsApp or Viber.

- Installing apps without the Play Store: Android allows users to install apps through third-party app stores like Amazon's App Store or manually by downloading APKs.

- Android rooting: Rooting an Android device gives users unrestricted access to the system files so that they can modify the software code. However, many apps (like banking apps, Google Pay, and some games) may not work on rooted devices due to security concerns. It also voids warranties on most devices and can lead to system instability if done incorrectly.

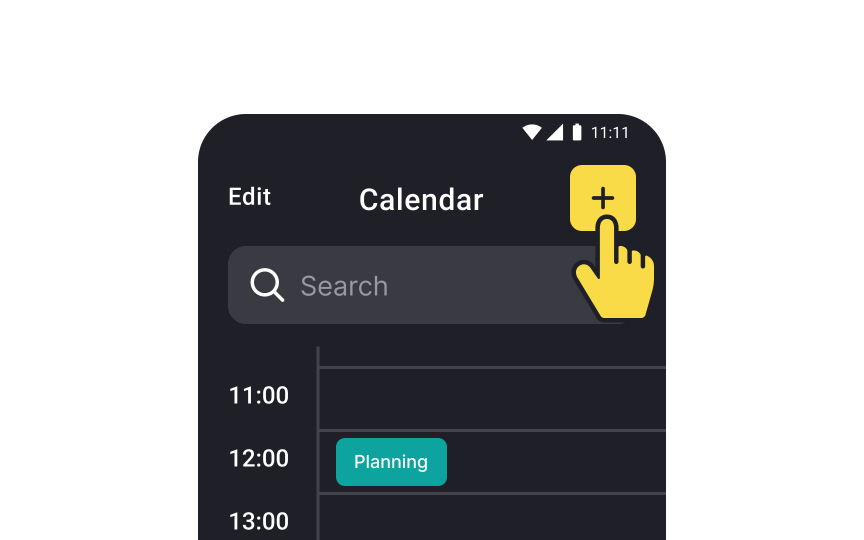

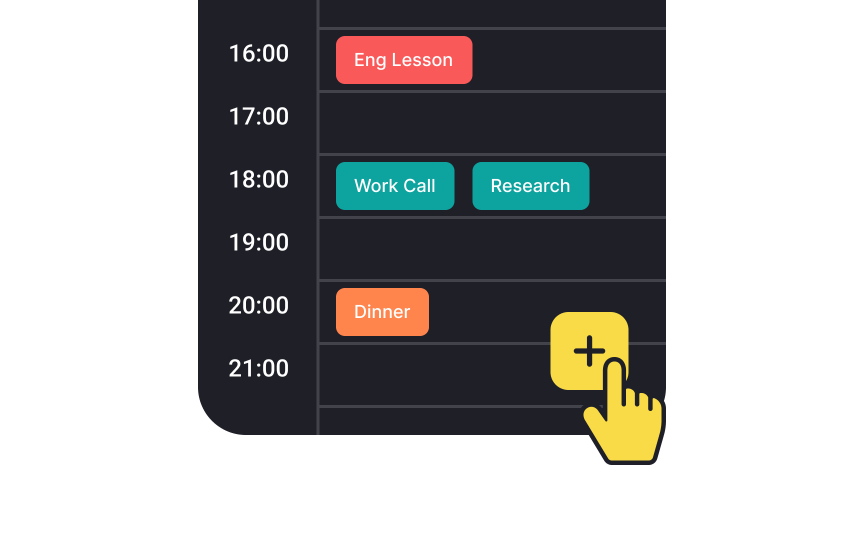

The floating action button (FAB) highlights the most important primary action on an

There are 3 FAB sizes to accommodate various

The button can be aligned left, center, or right, and positioned either above the

Note that touch targets extend beyond the visual bounds of an element. For example, an

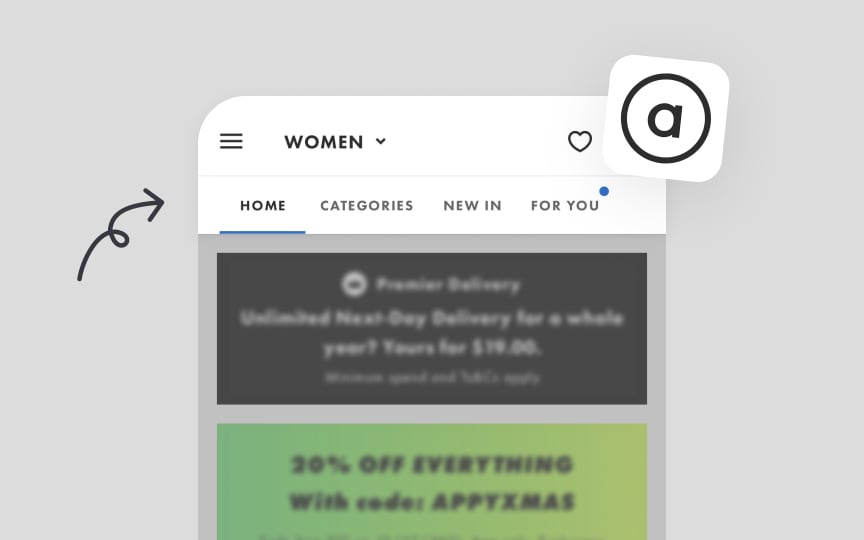

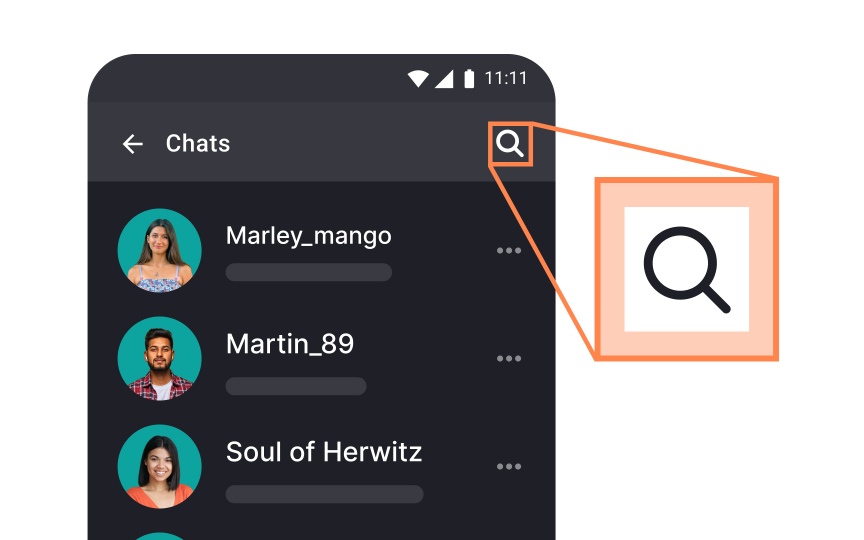

Tabs maintain a peer relationship, appearing side-by-side to show equal hierarchy level. While the interface can accommodate multiple tabs through horizontal scrolling, each tab should represent a distinct content category rather than sequential content. For example, music genres, product categories, or filter options work well as tabs.

Tab design focuses on clarity and scannability. Labels can combine

Roboto and Noto are the default typefaces on

Roboto has been refined extensively to work across a wider set of supported platforms. It's similar to iOS's San Francisco but has taller letterforms and a bit more breathing room. Noto's vertical metrics are compatible with Roboto.

Designers can also use custom

References

- FAB – Material Design 3 | Material Design

- Tabs – Material Design 3 | Material Design

- Typography – Material Design 3 | Material Design

Top contributors

Topics

From Course

Images provided by

Share

Similar lessons

Designing for Mobile Interfaces

Responsive vs. Adaptive Design