Elevation & Shadows in Design Systems

Define and apply elevation in a design system to create clear depth, hierarchy, and purposeful visual structure.

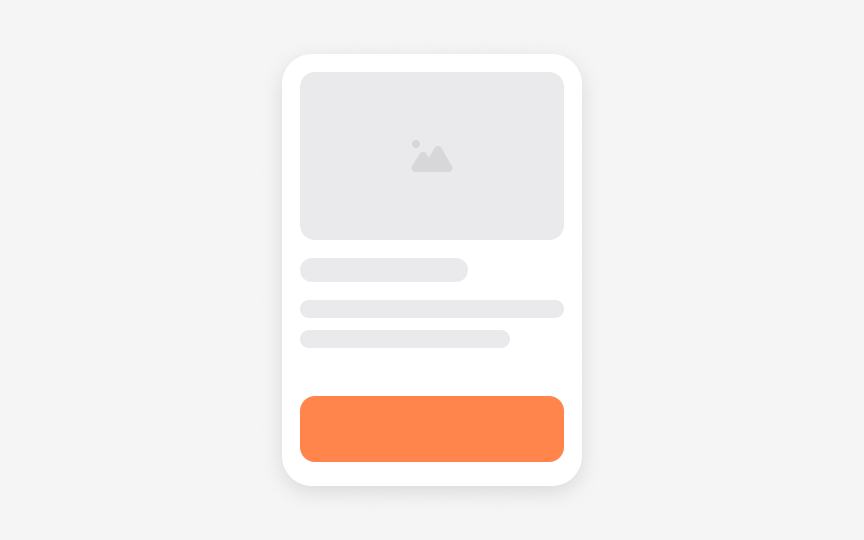

Depth is one of the easiest ways to guide the eye and signal interaction, focus, and hierarchy. A surface that lifts slightly feels important. A flat one fades into the background. Even before users interact with anything, elevation quietly tells them where to look and what matters most.

In a design system, this becomes a shared language. Instead of guessing which shadow to use or how high a card should appear, teams rely on clear elevation levels and matching shadows. These rules keep the whole product consistent, from basic layouts to overlays that sit on top of everything else.

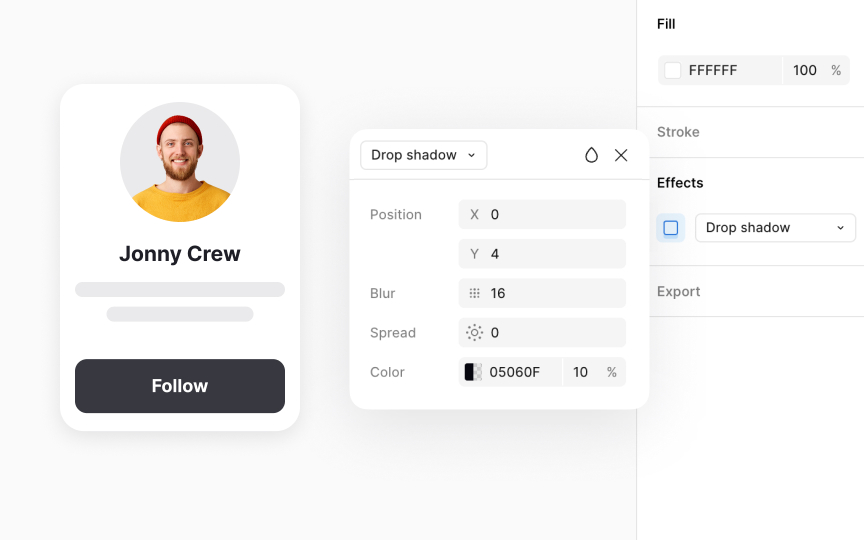

Shadows help bring this structure to life. They show where the light comes from, how far something sits from the surface, and when an element reacts to touch or motion. A small lift on hover or a deeper shadow during a drag can make the interface feel more responsive and intuitive.

Good elevation also supports accessibility. Shadows alone can be too subtle, so strong surface contrasts and meaningful steps between levels make depth easier for everyone to understand.

When elevation is treated as a system rather than decoration, it keeps interfaces calm, clear, and predictable. It gives every layer a purpose and helps teams build products that feel well-structured at first glance.

Elevation creates the illusion of depth in a flat interface by placing surfaces on different depth levels, often described as a virtual z axis. Elements that appear higher feel closer to the eye because

Elevation is not only about static hierarchy. Many design systems also use it to communicate

A

Pro Tip: When deciding which element should rise above others, compare their roles rather than their size. Priority comes from purpose, not from dimensions.

Realistic depth often depends on combining more than one shadow. Layering soft and sharp shadows together creates a natural glow around raised surfaces. A softer shadow can suggest ambient light, while a sharper one can signal directional light. This layered approach helps components feel grounded in their environment instead of floating unnaturally. Shadow

Light direction shapes how

Defined shadow positions help solve this problem. Systems often use left, right, or bottom shadows as standard placements. These positions are not decorative. They give each layer a clear sense of orientation so the interface feels grounded in the same environment. Keeping the light source stable also strengthens hierarchy because lifts and overlaps become easier to read at a glance.

Pro Tip: When choosing a shadow direction, check it on busy layouts. Inconsistent angles are easier to spot when many elements appear together.

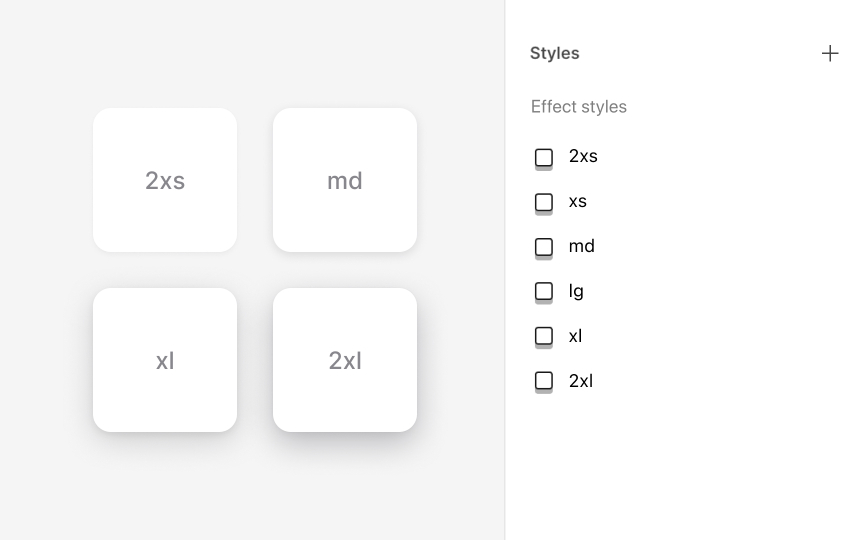

An elevation scale starts by turning

The scale becomes clearer when each level has a defined purpose. Lower levels often support base surfaces, mid levels hold cards or containers, and higher levels represent overlays and

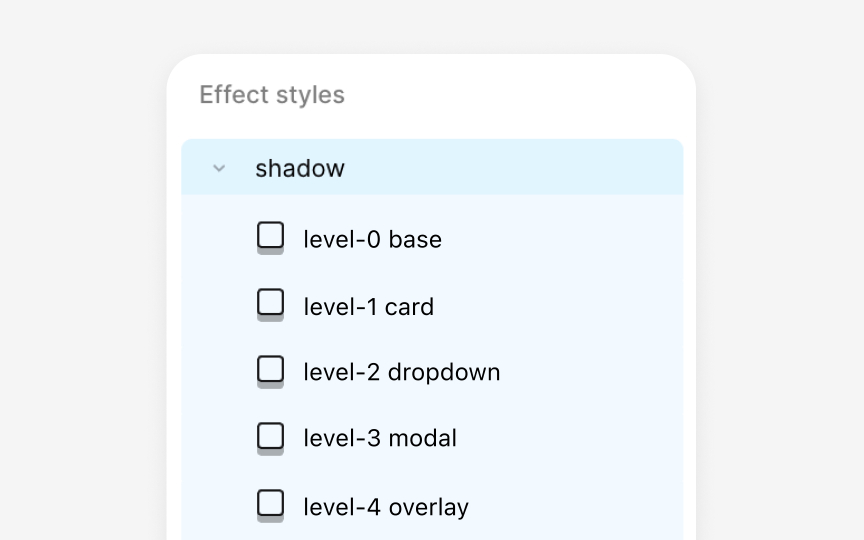

Keeping all elevation styles grouped in the Figma library makes the system easy to maintain. When a value changes, every component using that style updates automatically. This alignment between design tokens and code tokens helps teams keep depth predictable across screens and platforms.[3]

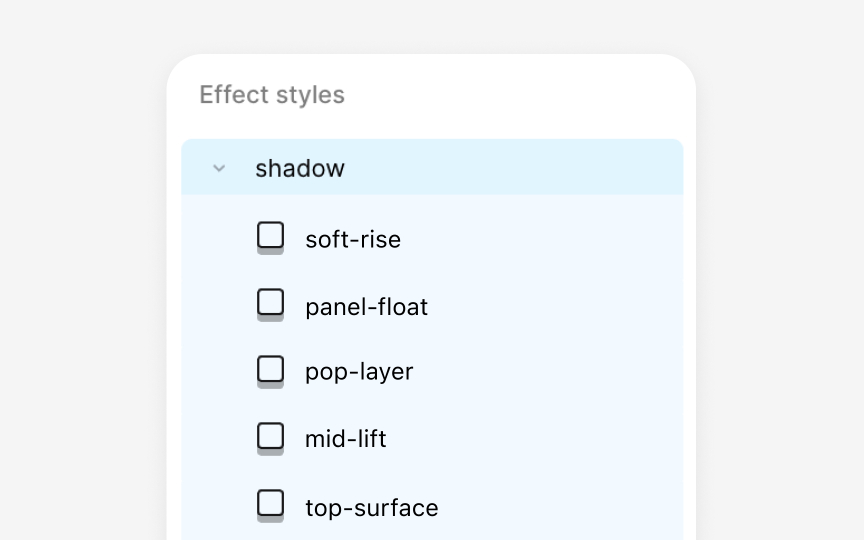

Naming elevation levels helps teams understand how each layer behaves without inspecting

Some systems pair numeric levels with functional labels to make the intent clearer. A combined name like ‘elevation-1 card,’ ‘elevation-2 dropdown,’ or ‘elevation-3

Naming also affects how elevation tokens work across platforms. When the same naming pattern appears in Figma styles, token files, and code, components gain predictable depth. Surfaces such as overlay or raised can then apply the correct tokens without custom adjustment, keeping complex layouts visually stable.

Shadow

Some

Pro Tip: When testing elevation in dark mode, focus on contrast between surfaces first. Shadows only support the effect when the surface tone is clear.

Elevation helps direct attention by making certain elements feel closer to the user. Increasing depth on an important surface naturally pulls the eye toward it. This is why raised elements often hold interactive components like cards, and why overlays use the highest elevation to interrupt the flow when something needs an immediate response.

Elevation also supports

Using elevation thoughtfully avoids visual noise. When too many surfaces are raised, the

Accessible elevation also avoids decorative shadows that do not represent real hierarchy. Extra shadows can create visual noise and draw attention away from important surfaces. Keeping elevation tied to meaningful roles reduces this confusion. Each level should support a specific purpose, such as separating a card from the background or highlighting a temporary overlay. A predictable structure helps more users rely on depth cues to navigate content, even when the interface becomes complex.

Pro Tip: If an elevation level feels unclear, adjust the surface tone first. A stronger contrast often improves readability faster than increasing shadow strength.

Similar lessons

Anatomy of UI Components

Atomic Design by Brad Frost