Working with Design Composition

Gain practical insights into working with design composition

All the compositional theory knowledge in the world will only get you so far if you don’t know how to apply it. Being able to identify and implement symmetrical vs asymmetrical designs, dynamic vs static compositions, geometric vs visual centers, etc., will make you a better designer.

While designs in the real world don’t always follow these compositional guidelines, the most effective ones almost always do. It’s smart for designers to understand how these compositional techniques work and when to use them.

Building your

When defining a compositional center, decide where your users' eyes should go first. You can achieve balanced and stable

A visually centered

Which element within a

For example, a

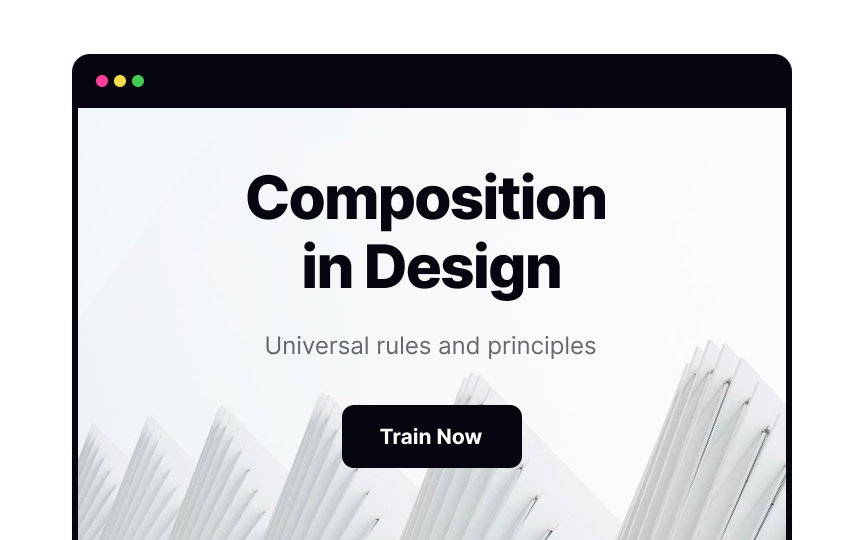

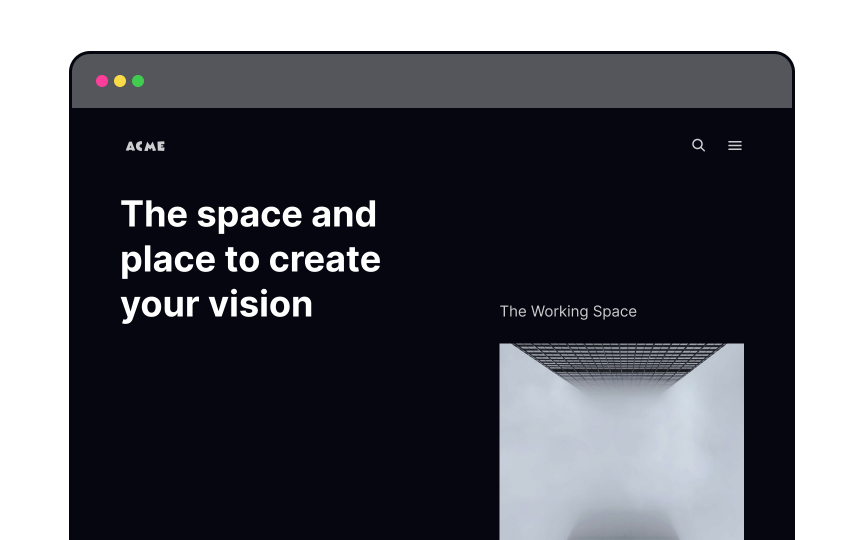

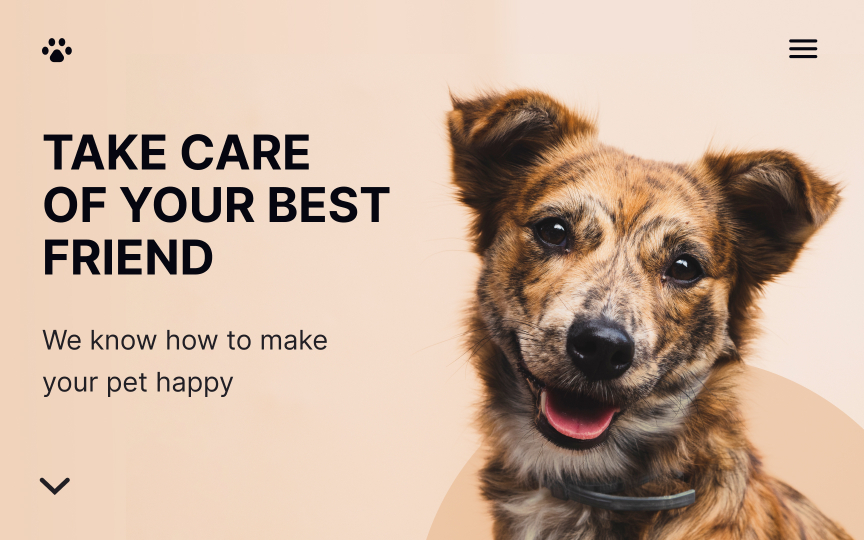

Symmetrical

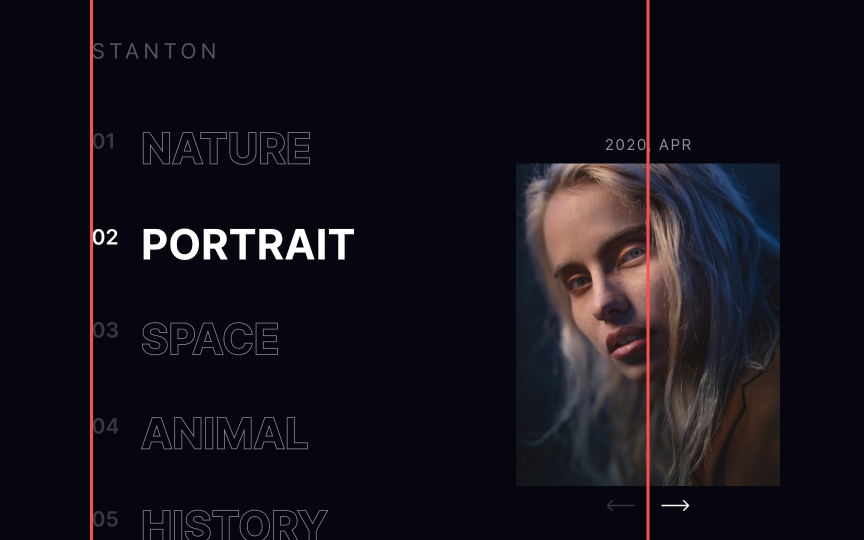

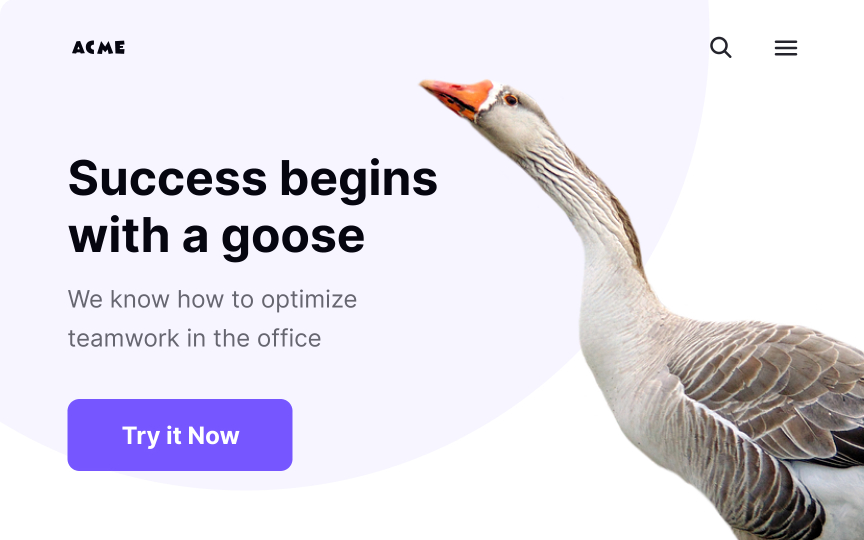

Symmetrical interfaces are well-suited to particular digital projects, such as a website devoted to one product or an artist’s portfolio. They’re an elegant solution and also easier to create than asymmetrical compositions.

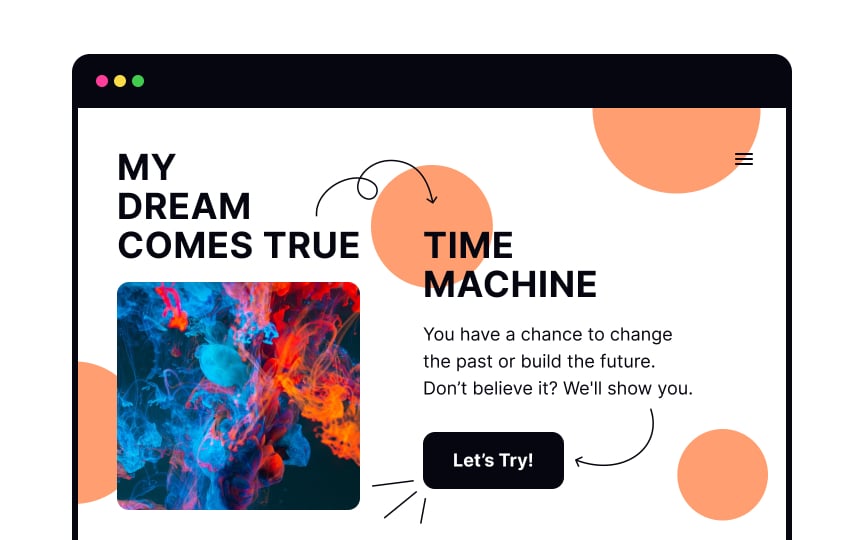

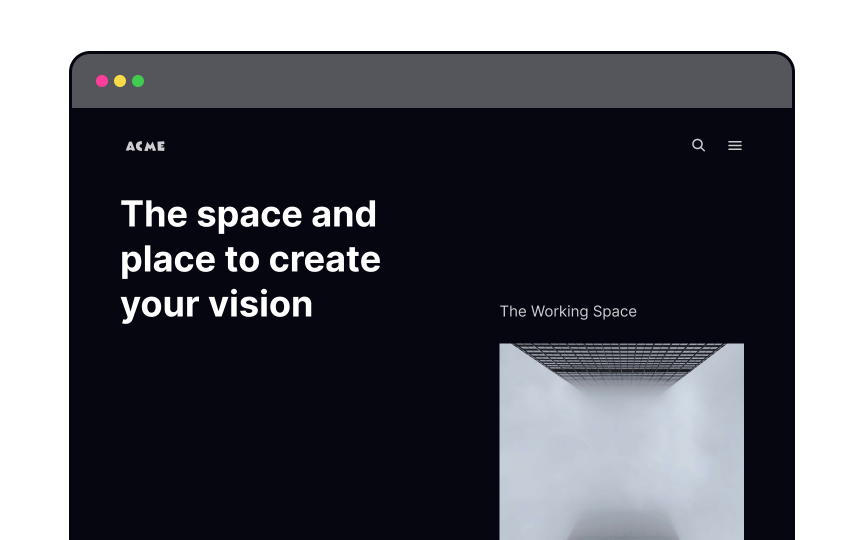

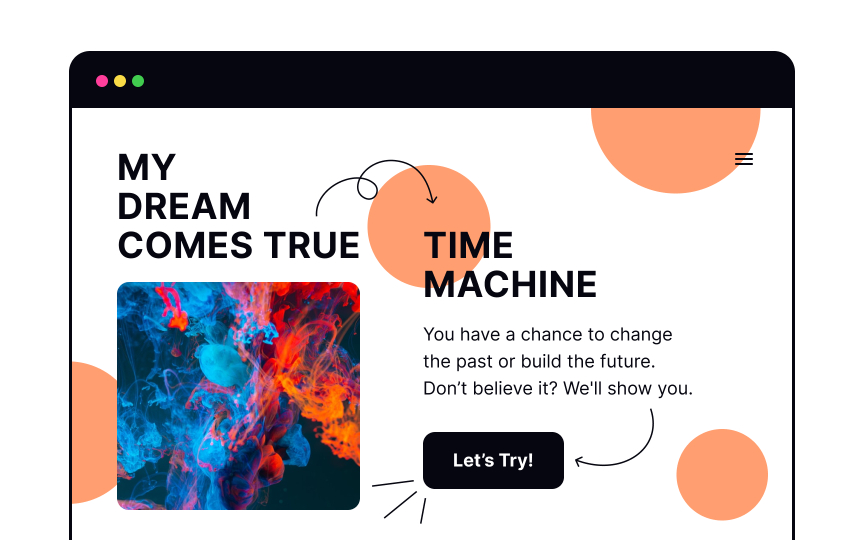

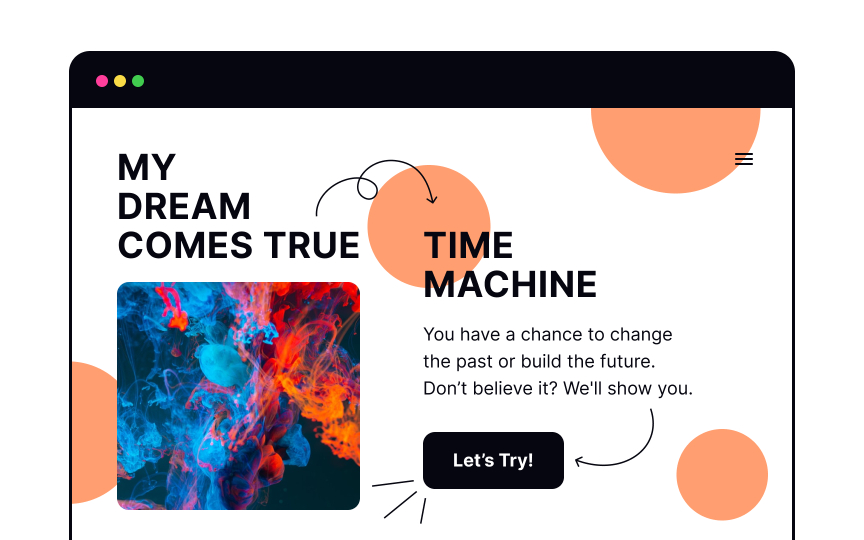

Asymmetrical compositions are well-suited for more complex and exciting designs with several focal points. They’re also more difficult to do well than symmetrical compositions since there’s no mathematical formula for creating them — they rely on a designer’s eye instead.

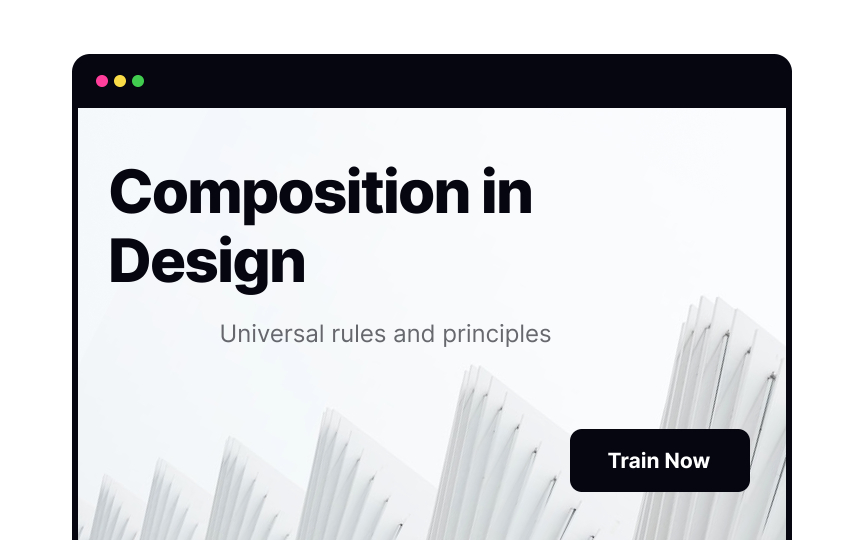

In this example, the headline on the left is the main focal point for the design, while less significant focal points — the subhead and CTA

Closed compositions arrange all elements within a (mostly invisible) frame.[3] They provide a sense of completeness. When users look at a closed

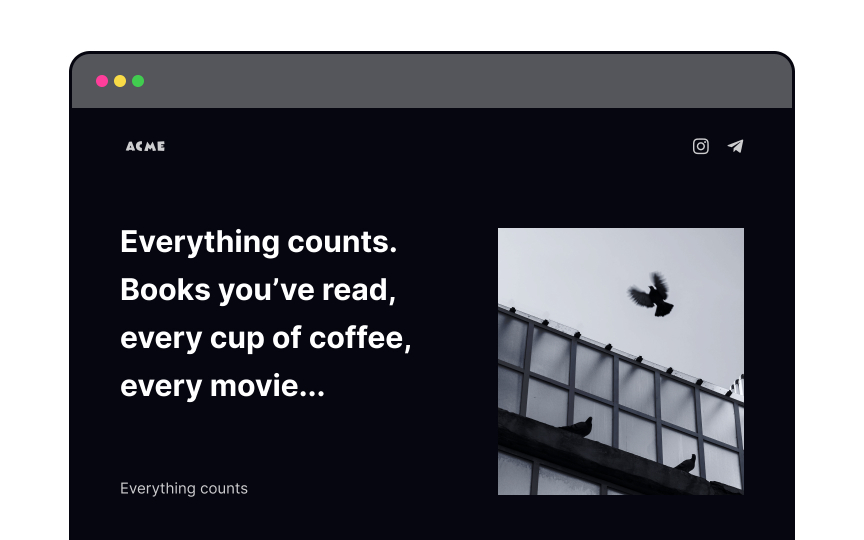

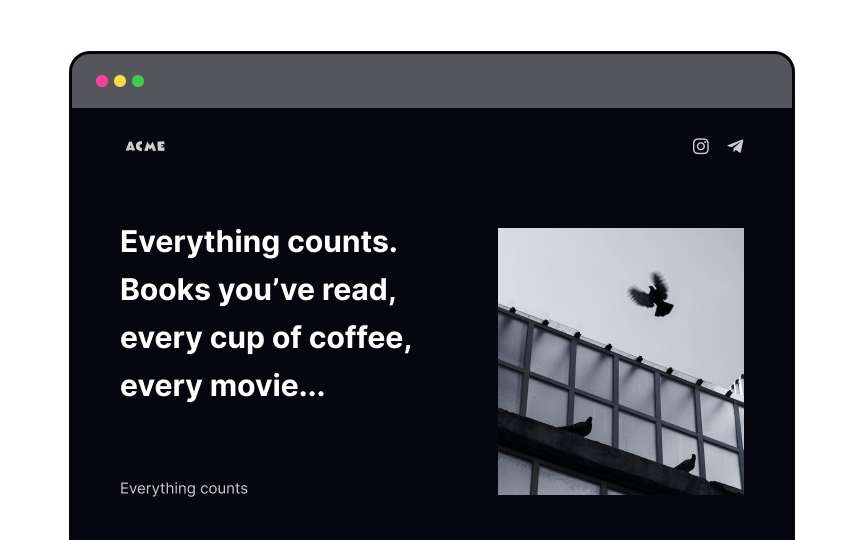

Open

Open compositions are like ongoing stories that intrigue users to scroll and explore. They’re perfect for

Pro Tip: Use open compositions for websites with long and text-heavy pages.

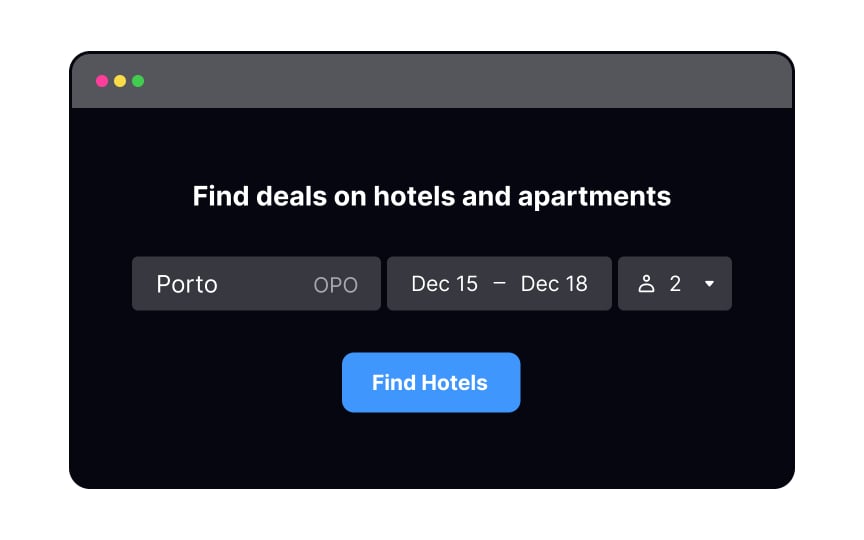

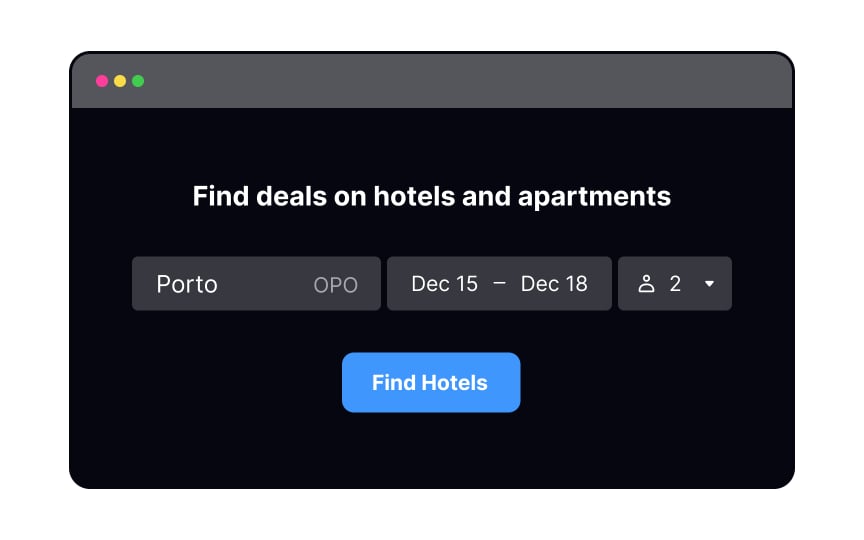

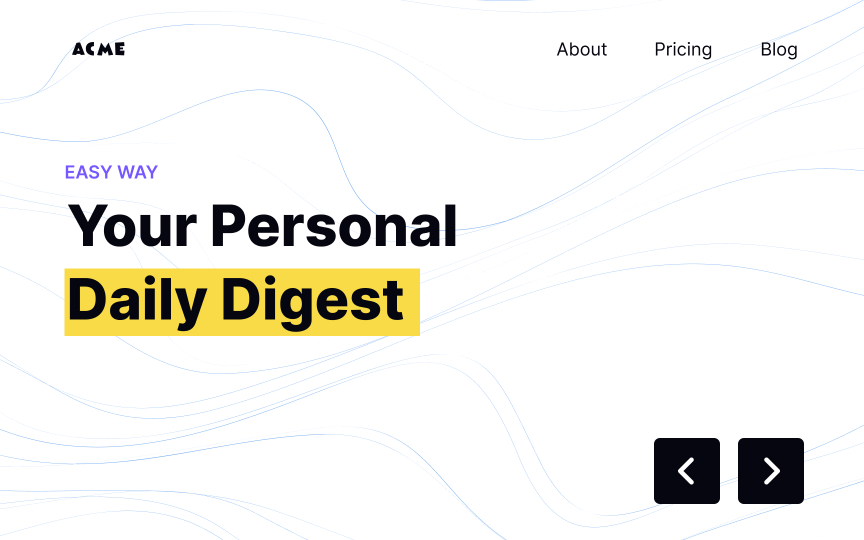

Static

Use static compositions to organize blocks of information that need to be easy to scan, like forms or infographics. Because of their stable nature, they’re well-suited to activities users might consider high risk (such as making a purchase or reservation).

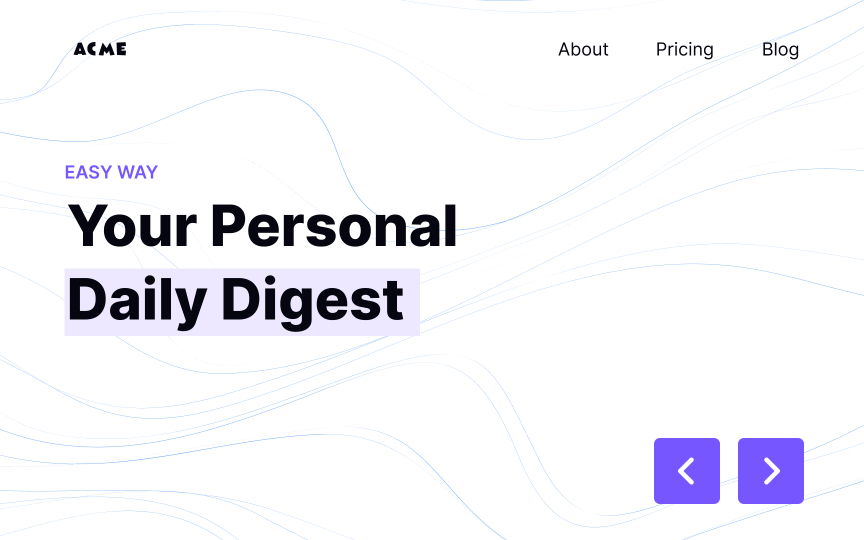

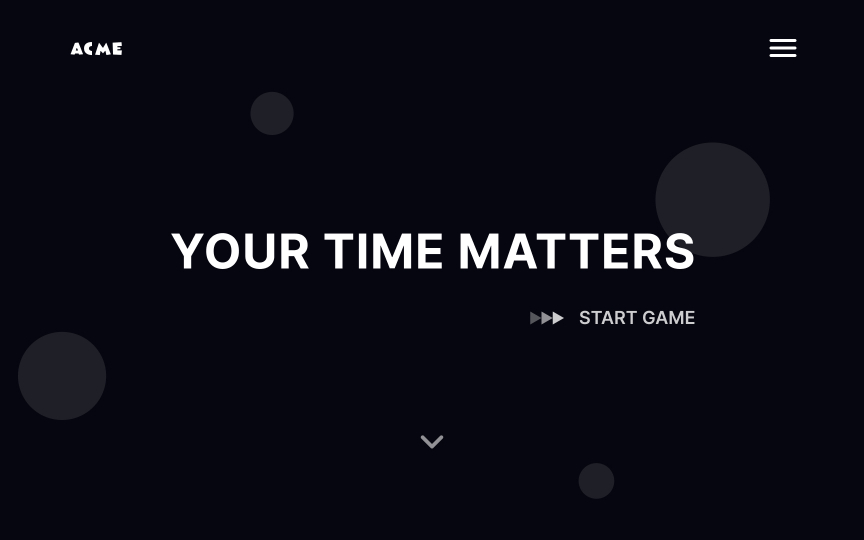

Our eyes instinctively look for balance, and unbalance unsettles us. The irregularities of dynamic

Dynamic compositions are a powerful tool that can guide users through your design and help them embark on an exciting user journey. Use them when you want your users to feel energized by your products.

Compositional balance is about an even distribution of visual weight. To achieve it, play with the size, shape, and

Pro Tip: Balance doesn't equal symmetry — it can be achieved with asymmetric composition, resulting in more complex and intriguing designs.

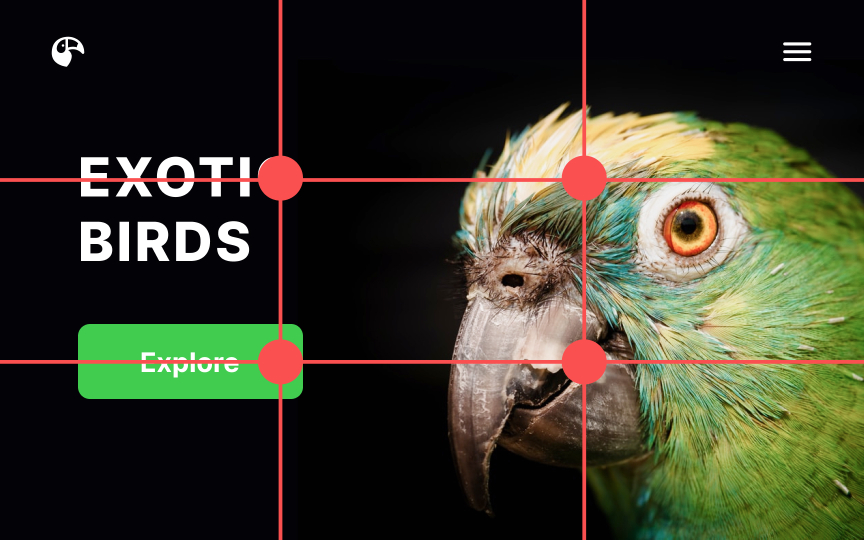

The rule of thirds is a fantastic compositional tool that came to digital design from the world of photography. Imagine the screen divided into equal horizontal and vertical thirds by invisible lines. Our gaze intuitively gravitates toward the intersections of those lines.

According to the rule of thirds, those intersection points are the ideal spots to place key elements, like

Designers use leading lines — similar to grid lines — as a scaffold to build their compositions around. They work because our eyes are naturally drawn to follow the lines within a design, even when the lines themselves are invisible.[6]

Unlike grids, leading lines provide more freedom in creating unconventional, outstanding

As the name suggests, a 1-point

Pro Tip: This type of composition is great for concise designs that aren't overloaded with information.

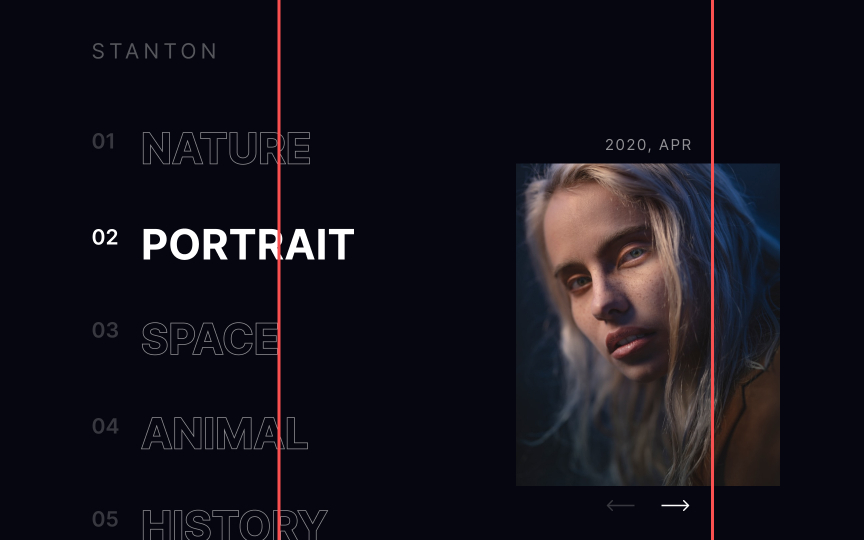

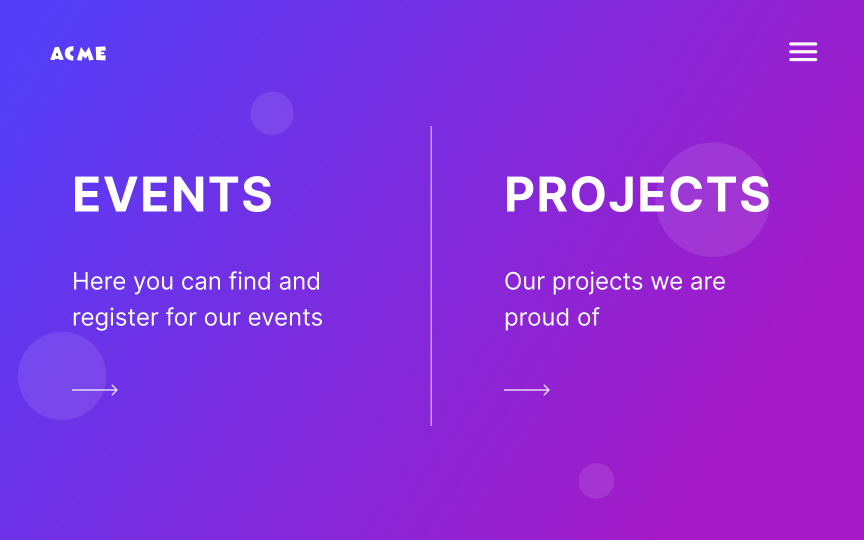

Designs with two compositional centers have two main areas that draw attention. Instead of one focal point, the viewer’s attention moves between these two areas. When elements on the left and right are visually balanced in size, weight, or spacing, the

3-point

Upward triangles create a sense of stability and strength and can provide a sense of unity to your design. Downward triangles, on the other hand, are exciting and create a sense of movement and even urgency.

Pro Tip: 3-point compositions are often used for home pages — with focal points being the headline, the hero image, and the CTA button.

4-point compositions generally create a frame on the

The different focal points can compete for user attention, so use this type of composition with care. They’re great for things like product listings or other pages where

Pro Tip: Because of their stable, focused structure, 4-point compositions are great for graphs, tables, and forms.

References

- Geometry in UI Design | Medium

- Designing Using a Visual Center | The Paper Blog | The Paper

- The Rule of Thirds: Know your layout sweet spots | The Interaction Design Foundation

Top contributors

Topics

From Course

Share

Similar lessons

Intro to Design Layouts

Intro to Design Grids