Defining Problems for Effective Specifications

Frame real problems and analyze user insights to guide meaningful product decisions.

Before drafting any specification, product teams must first understand what problem they are solving and why it matters. Many failed projects start with assumptions rather than evidence. The key to avoiding this lies in defining the problem clearly and grounding it in real user feedback.

Problem definition transforms vague challenges into focused, measurable goals. It begins with identifying gaps between the current and desired states and articulating who is affected and how. A clear statement should describe the issue, its impact, and the intended outcome without jumping to solutions.

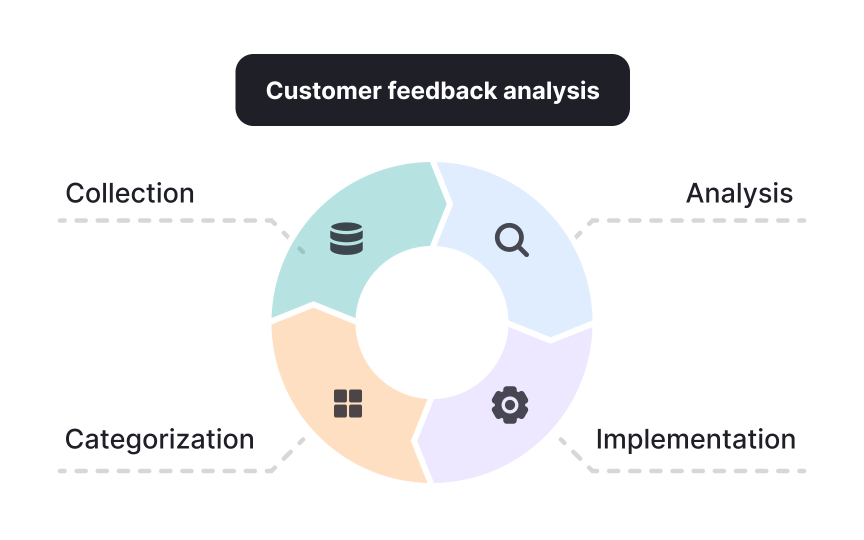

Once the problem is defined, feedback analysis provides a reality check. User responses reveal pain points, priorities, and unmet needs that refine both the problem and the direction of future specs. Structured analysis (collecting, categorizing, coding, and sharing feedback) helps teams translate raw opinions into actionable insights.

By mastering problem definition and feedback analysis, product teams set the foundation for writing precise, relevant specifications that address real needs rather than assumptions.

Before writing a specification, teams need to clearly define the problem they are solving. A well-framed problem statement describes the issue, its impact, and the desired outcome. It serves as a foundation for product specs by keeping every decision focused on solving the right challenge. Without it, teams risk creating specifications filled with unverified assumptions or features that do not address real user needs.

A clear problem definition also aligns product, design, and engineering around a shared goal. It explains why the work matters and how success will be measured. In product documentation, this understanding prevents scope creep and confusion later in the process. When the problem is defined first, the specification that follows becomes more purposeful, structured, and connected to measurable results.

Pro Tip: Define the problem before drafting specs to ensure that every detail later connects to real goals and measurable outcomes.

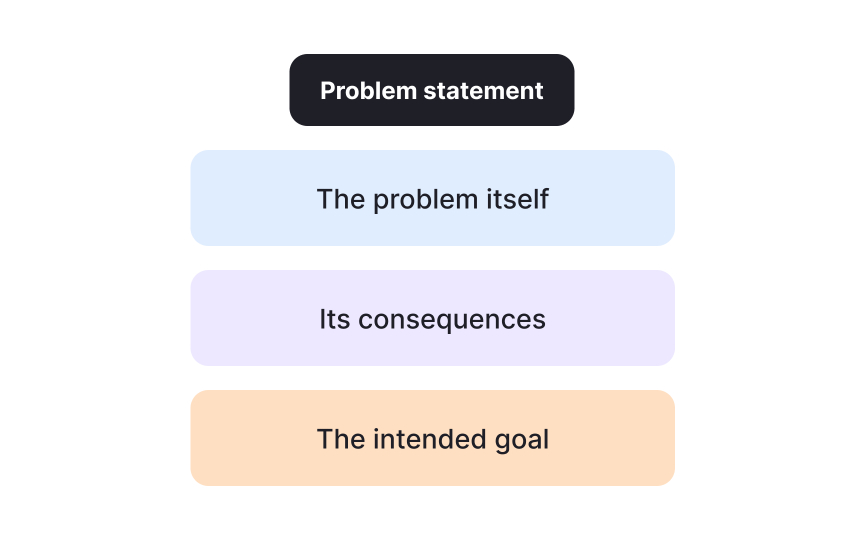

Every specification needs a solid starting point: a structured problem statement. It usually includes 3 essential parts:

- The problem itself

- Its consequences

- The intended goal

The problem defines what is happening and where the gap exists between the current and desired state. The consequences describe the negative outcomes this issue creates for users or the business. The goal sets the direction by outlining the improvement to be achieved, not the exact solution.

This structure helps teams translate observations into a clear framework for specs. For instance, when defining a feature request, the spec should link each requirement to one of these three components. Doing so keeps technical and design decisions tied to verified needs and measurable results. A structured statement also helps prevent bias by separating the problem from the solution, allowing later stages of the spec to focus on how to achieve that goal effectively.[1]

Pro Tip: Keep each part short and factual. Describe the problem, its effect, and the target outcome before discussing solutions.

A well-written problem statement shapes the entire specification. It defines what needs to be solved without prescribing how to solve it. To stay effective, it should be short enough to read quickly but specific enough to show a clear understanding of the issue. It must also remain focused on facts, not assumptions. Vague phrasing like “the process is inefficient” or “users are unhappy” weakens the statement because it hides the true cause and measurable impact of the issue.

A strong statement avoids embedding solutions inside the problem. Instead of writing “we need to redesign the app interface,” a more accurate phrasing would be “users fail to complete purchases because navigation between product and checkout pages is unclear.” The second version identifies a concrete obstacle and its consequence, leaving the design of a solution for the next step in the specification. By keeping the statement neutral and specific, teams make it easier for every part of the spec, such as goals, requirements, or success criteria, to align with verified user and business needs.

Pro Tip: Replace general phrases with observable facts that show what fails, where, and why it matters.

Many specifications fail not because the team lacked ideas but because the problem was defined poorly. One frequent mistake is describing symptoms instead of causes. For example, low user retention may be a symptom, but the real problem could be unclear onboarding or missing value in the product experience. Another issue arises when statements are too broad, such as “we need to improve user experience.” Without specifics, the spec becomes an endless list of tasks with no measurable focus.

Problem statements can also fail when they mix business desires with user goals. A team might define a problem as “we need to increase revenue,” which is an outcome, not a problem. A better version would connect business impact to user behavior, such as “users abandon the

Pro Tip: Focus on what truly causes the issue, not just on its visible effects. A well-defined problem naturally guides better specifications later.

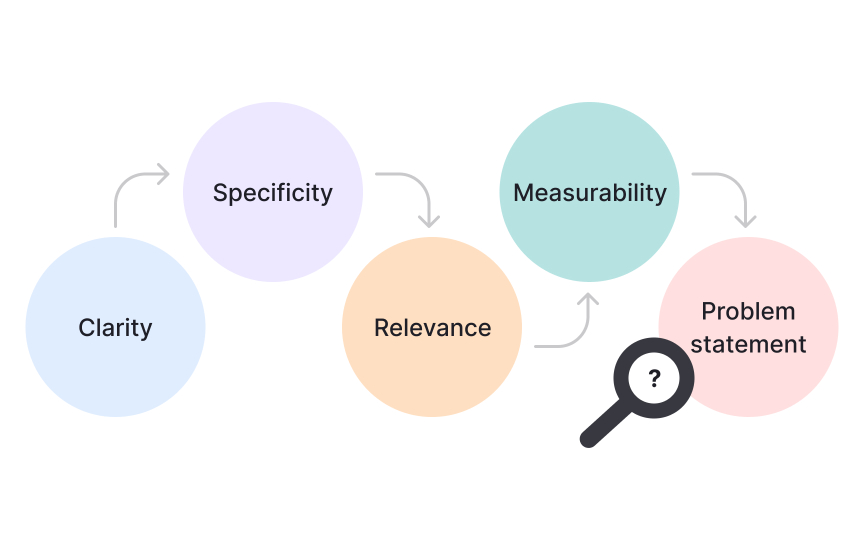

Even a well-written problem statement should be tested for clarity and focus before it becomes part of a specification. A simple check is to see if anyone reading it, whether from design, engineering, or leadership, can understand the issue without extra explanation. A clear statement shows what the problem is, who it affects, and why it matters. If any of these parts are missing or unclear, the statement needs refinement.

Clarity testing can also include verifying whether the statement describes the problem without suggesting a solution. For instance, “users can’t access saved settings after logout” defines a clear issue, while “the login system needs to be rebuilt” already proposes how to fix it. The first version leaves space for the specification to define the solution later. Testing the clarity of the problem definition ensures that the final specification builds on a well-understood, fact-based foundation.

Pro Tip: Ask others to restate the problem in their own words. If interpretations differ, the definition is still unclear.

After the problem is defined, it needs to be verified through user feedback. Feedback confirms whether the issue described in the problem statement reflects real experiences. It can come from surveys, interviews, website forms, social media, or feedback widgets that let users leave comments directly within the product. Collecting these inputs in one structured place allows the team to identify patterns and confirm whether the defined problem matches what users actually face.

Organizing feedback systematically helps separate valuable insights from general opinions. Grouping responses by urgency, topic, or customer segment highlights which problems have the strongest impact and should be prioritized in the specification. This process ensures that the spec does not rely on internal assumptions but on evidence drawn from real user data. When the feedback confirms the problem’s importance, it strengthens the foundation for all following sections of the specification.[2]

Pro Tip: Store user feedback in one shared workspace and look for repeating patterns before finalizing the problem in the spec.

Collecting user feedback is only the first step. To make it useful for specifications, teams must organize and prioritize it. Categorization means grouping similar insights together by themes such as usability, pricing, bugs, or performance. This structure reveals where users face the most critical pain points. Prioritization then helps decide which problems require immediate attention and which can wait. Urgency, business impact, and frequency of mentions are key factors that guide this process.

For example, if multiple users report issues that block them from completing purchases, that feedback should take priority over minor requests for personalization. Sorting feedback this way ensures that specifications focus on solving the right issues first. Categorized and ranked insights give clarity on what should appear in the “problem” or “context” section of the spec, creating a direct

Pro Tip: Rank user problems by impact and frequency. The most common and harmful ones should shape the next product spec.

Categorization gives structure to feedback, but coding makes it measurable. Coding means labeling similar comments with short, consistent tags that describe the issue in concrete terms. For instance, comments like “the payment

This transformation from qualitative to quantitative data helps teams spot trends and define problems supported by evidence. Instead of general claims such as “users experience technical issues,” a spec can include precise findings like “45 percent of reports mention checkout error.” This makes the specification clearer, more persuasive, and easier to align across teams. Coding also simplifies future tracking, allowing teams to measure whether later fixes reduce the same complaints.

Pro Tip: Create short, consistent codes for recurring issues. Use them in specs to show frequency and strengthen problem statements with data.

After coding and organizing user feedback, the next step is synthesis. Synthesis means combining patterns and data points into clear insights that validate or reshape the original problem definition. When recurring issues appear across feedback categories, they confirm where the biggest gaps exist between the current and desired experience. This process helps refine the initial problem statement, turning raw opinions into structured evidence.

In product specifications, this refined statement becomes the anchor for defining goals, metrics, and success criteria. It explains why the product or feature is needed and which user problem it will solve. Without synthesis, feedback stays fragmented and difficult to apply. By transforming findings into a clear statement of need, teams ensure that the spec remains rooted in user evidence, making it both persuasive and measurable.

The final step is linking problem insights directly to the structure of a specification. A spec should begin with a clear summary of the validated problem, followed by measurable goals and potential acceptance criteria. Each requirement in the document should trace back to this definition, ensuring that the proposed features, designs, or technical changes all contribute to solving the identified issue.

Connecting the insights this way gives the specification purpose and credibility. It shows that the work is not based on assumptions but on evidence drawn from real user feedback and problem analysis. This alignment also creates a feedback loop: once the solution is implemented, new data and user responses can be compared to the original problem statement to evaluate success. In this way, the specification becomes not just a plan but a living reference for understanding progress against clearly defined needs.

References

Topics

From Course

Share

Similar lessons

Understanding User Needs and Pain Points

User Research and Personas