Repetition & Contrast in Typography

Discover the power of repetition and contrast in typography, as they play crucial roles in creating visually engaging and effective designs

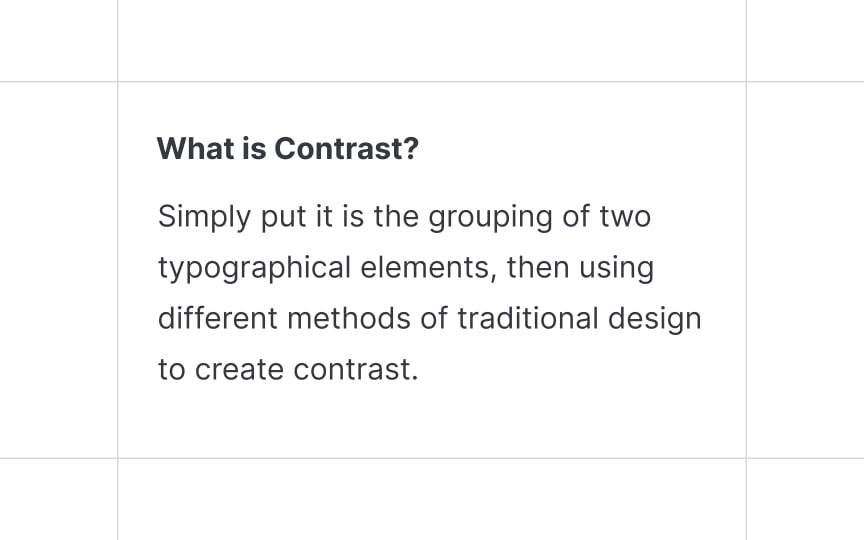

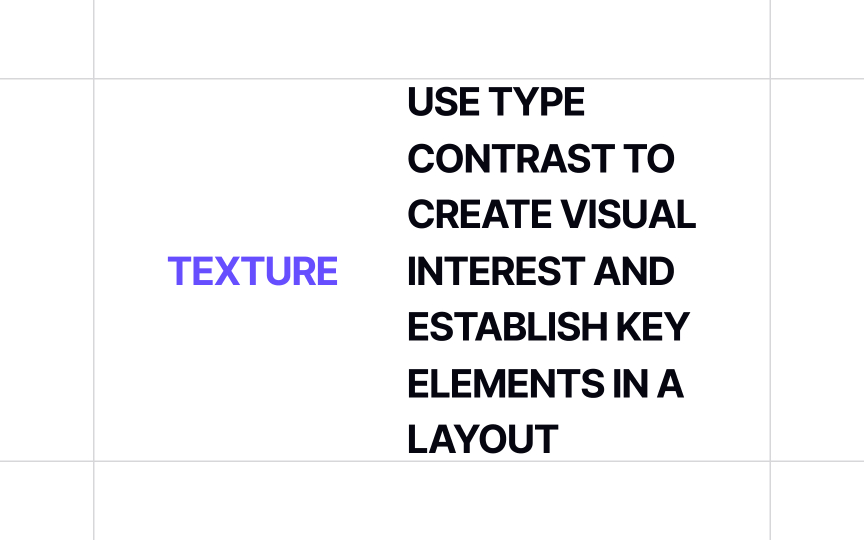

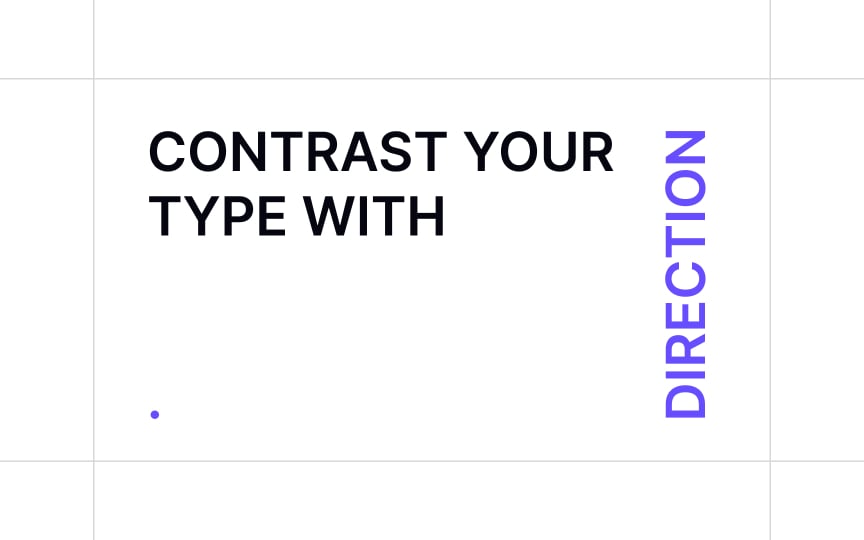

What is more exciting to look at: an interface with one primary color and one typeface or a balanced combination of matching colors and appropriate fonts? That's the benefit of contrast. Designers can use typography to reinforce visual interest through the use of contrasting elements. Size, font weight, color, form, texture, direction — you can combine these methods to create aesthetically pleasing type compositions. Good contrast adds to the visual hierarchy that tells users what's important on a page and where to look at.

Canadian graphic designer Carl Dair was also one of the most prominent typographic designers of the 1950s and 1960s and is considered the father of modern typography. In his book "Design With Type" (published in 1952; revised and expanded in 1967), he suggests 7 types of contrast in typography that modern designers continue using in their works.

We use

According to Carl Dair, a Canadian designer and author of the book Design With Type, there are 7 principles of contrast in

Size is one of the most common yet powerful methods of

Contrast in size contributes to the

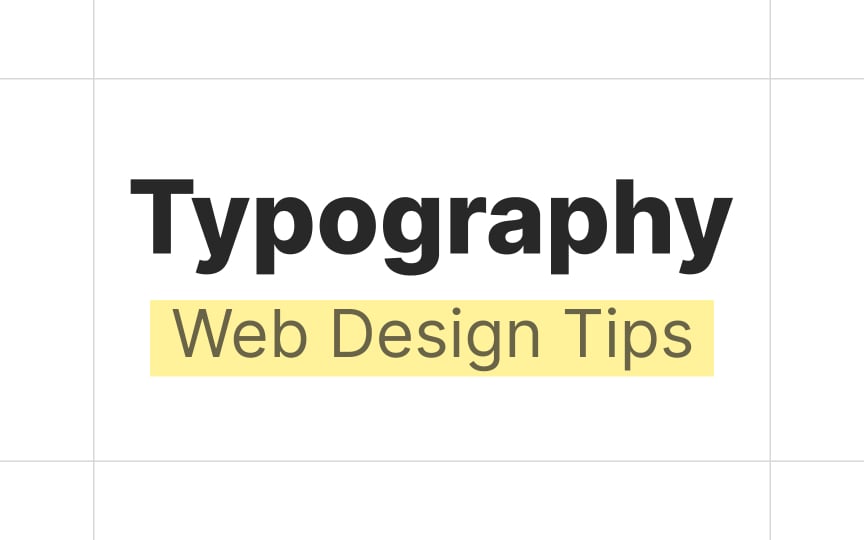

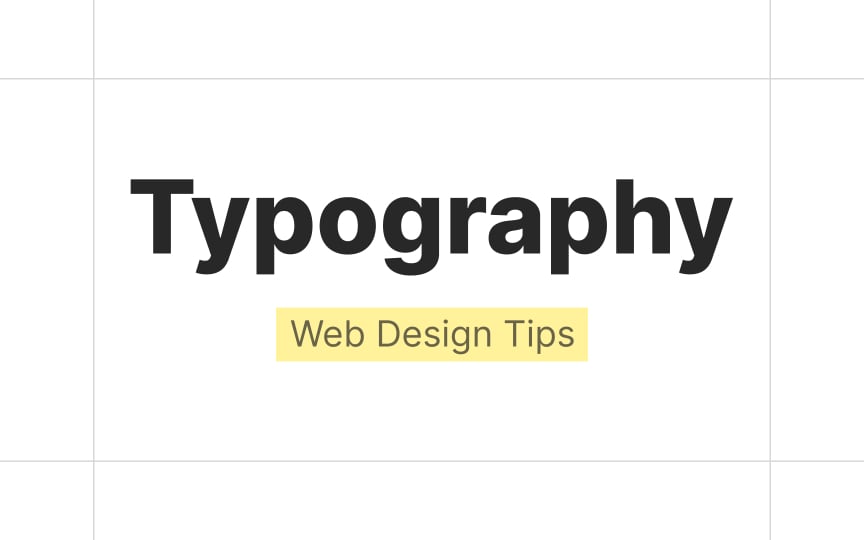

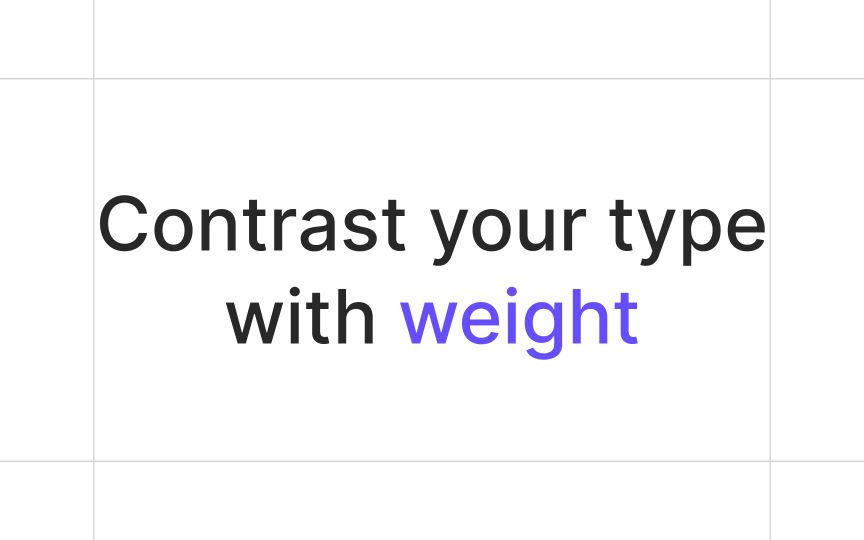

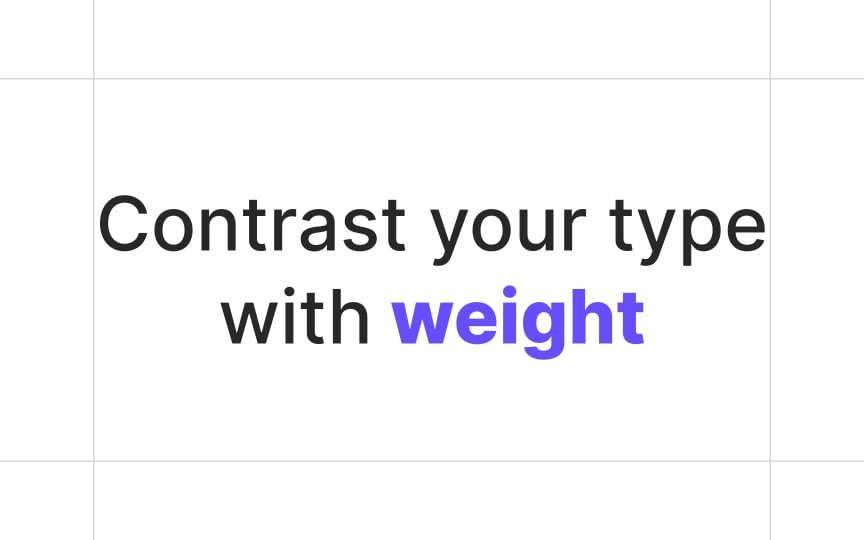

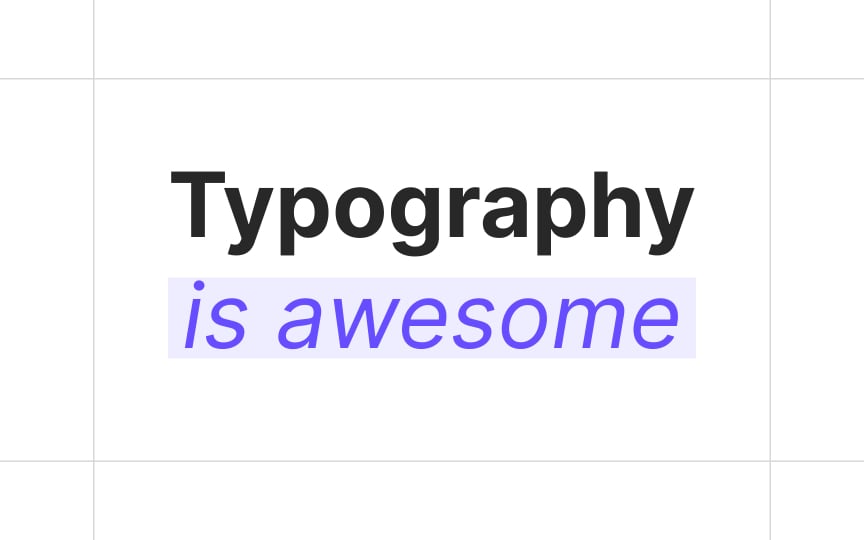

By making text bold — increasing its weight — you make it stand out among lighter and thinner type. Designers use heavier weights for headings, subheadings, keywords in the running text, or any type of text that requires special attention.

Weight can create a certain mood: heavy text appears more solid and impactful and is supposed to attract, alert, shock, or persuade. Use caution, though: too much weight can make type look too dramatic and even hurt text readability.

Weight is often used to strengthen the

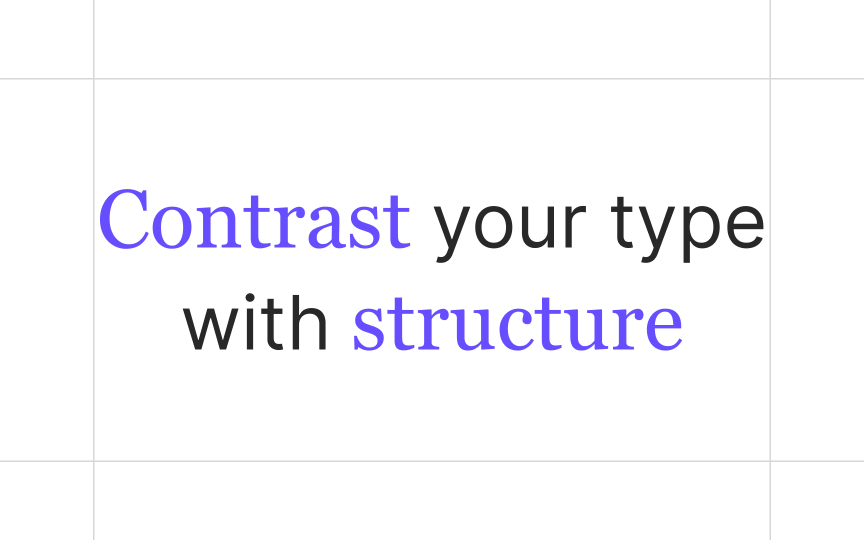

Using

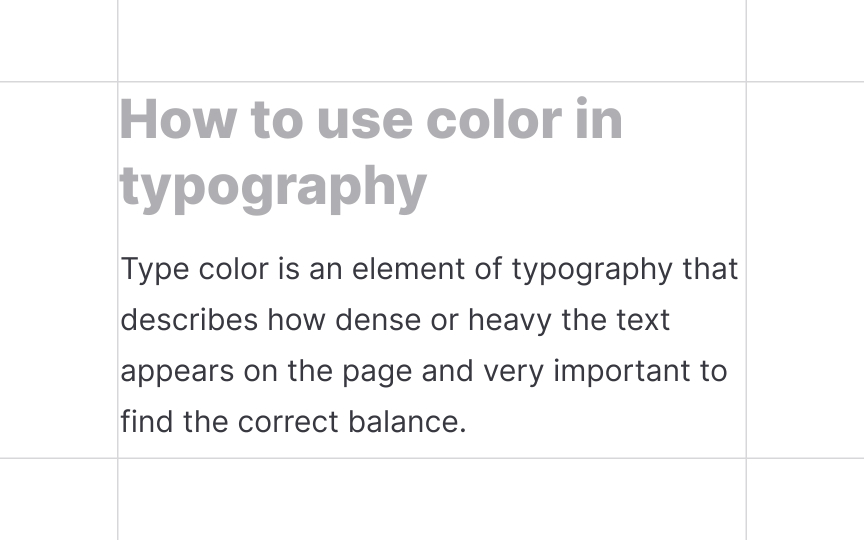

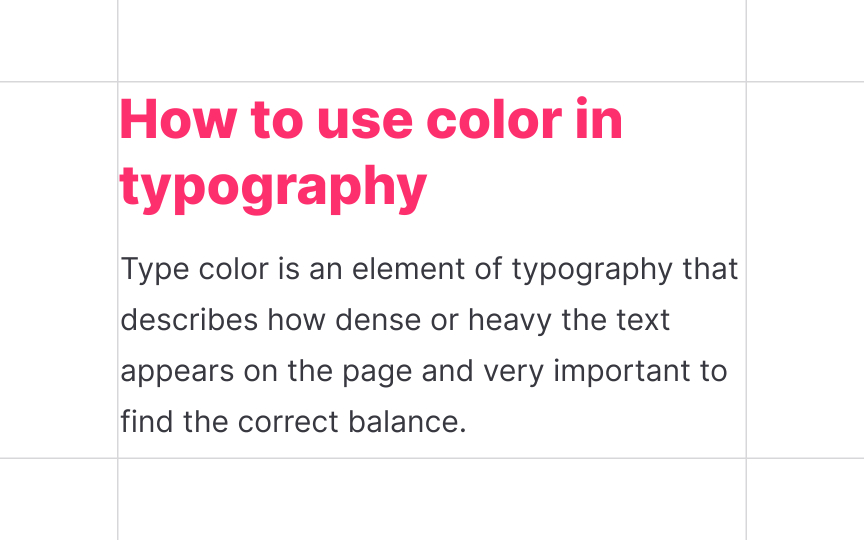

When we talk about the

Also, if stepping away from the traditional dark font/white background formula, think carefully when selecting and combining colors. They should create the right mood, communicate the message, and reinforce brand identity, while maintaining readability.

Pro Tip: Avoid relying solely on color to create contrast and draw attention. Users with some visual impairments will have trouble spotting the difference and may overlook an error or warning.

In

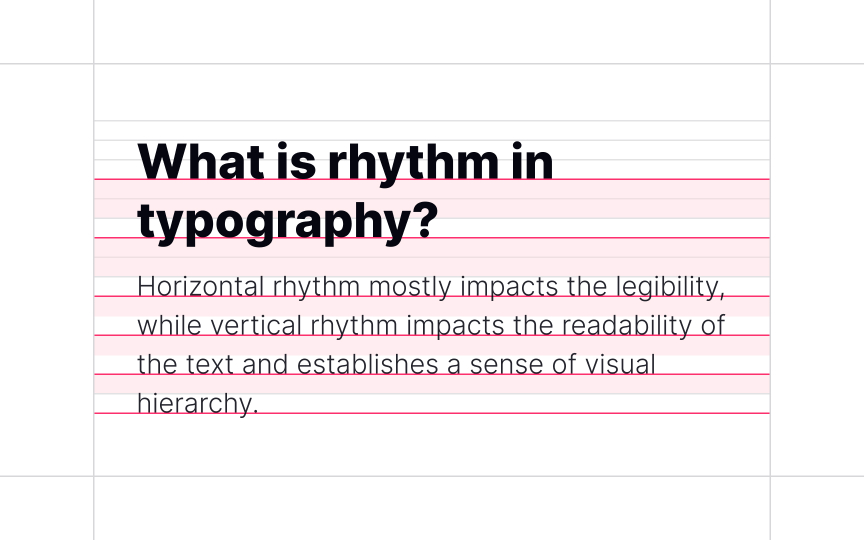

- Horizontal rhythm: Horizontal rhythm refers to letter spacing (tracking) and kerning and mainly contributes to legibility.

- Vertical rhythm: Vertical rhythm refers to space between paragraphs and line spacing.

Both types impact readability and create a sense of