The Art of Prioritization

Prioritize product ideas effectively to balance user needs, business goals, and limited resources.

Prioritization in product management is not a matter of choosing between good and bad ideas but of deciding which valuable opportunities deserve focus now and which must wait. Teams face more requests than they can ever deliver, and without a clear method to sort them, effort spreads thin and outcomes lose impact.

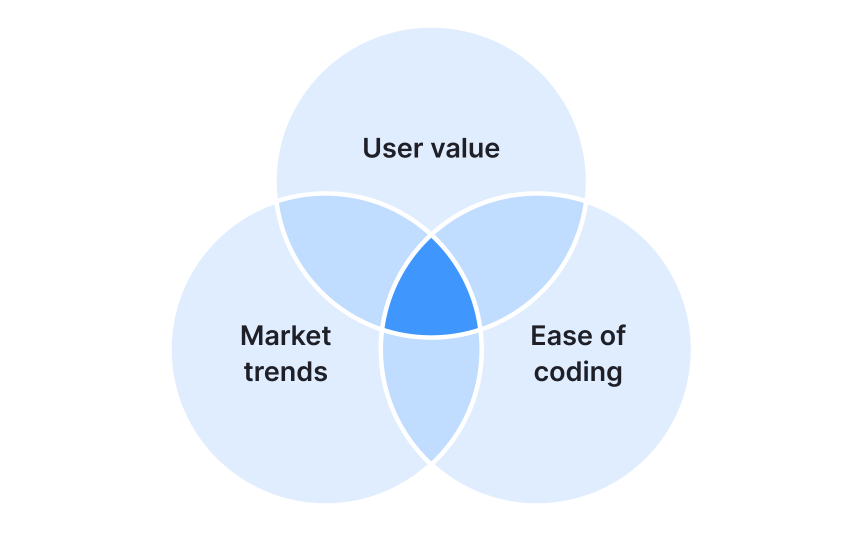

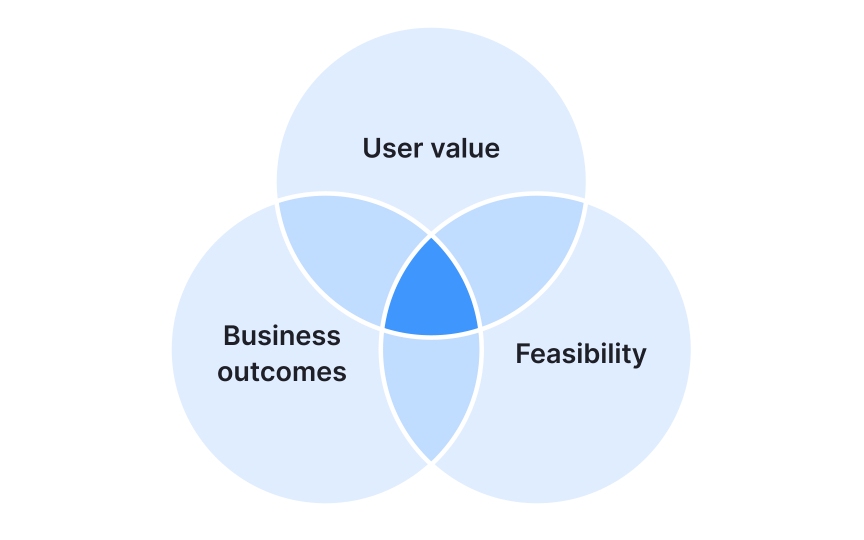

The discipline of prioritization ensures that decisions connect to strategy, not just to the loudest voice in the room. It brings structure to backlogs that would otherwise grow uncontrollably, and it helps prevent teams from becoming feature factories that deliver output without creating real value. By weighing user needs, business goals, and technical feasibility, prioritization channels attention toward work that drives meaningful results.

Saying “no” becomes part of this discipline. It is not a rejection of ideas but a way of protecting focus and maintaining direction. Prioritization is also continuous, adapting as new information, customer feedback, and market conditions emerge. Practicing it well enables product managers to defend decisions, align stakeholders, and keep the product moving toward its vision instead of being pulled in every possible direction.

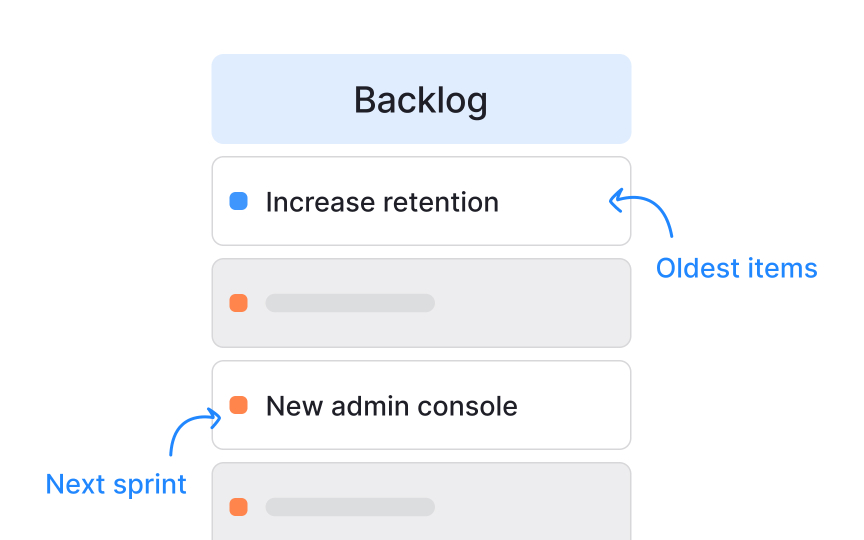

Every product team faces more requests than it can deliver. Executives bring new features they believe will capture revenue, engineers highlight technical debt, and customers request fixes or enhancements. This flood of input creates a backlog that easily grows beyond control. Without a system for filtering, it stops being a strategic guide and turns into a dumping ground where urgent and trivial items sit side by side. Overloaded backlogs confuse teams about what to tackle next and delay meaningful progress.

Recognizing this reality is not about dismissing ideas. Many suggestions may be useful, but they cannot all be pursued in parallel. Attempting to do so scatters resources and leaves half-finished initiatives that deliver little value. Understanding the backlog as a funnel rather than a storage bin is key. Items must be captured, but only a fraction should advance toward near-term action. The rest belong in structured secondary lists, so that attention remains on what will directly affect users and the business in the coming cycle.[1]

Pro Tip: Capture every idea but avoid treating them all as immediate tasks. Structure is essential to prevent backlog overload.

Without

Prioritization reframes the conversation. Instead of asking “What can we build next?”, the focus becomes “Which problems deserve solving now, given limited resources?” Decisions are weighed across user needs, market demand, and feasibility. This approach prevents teams from overcommitting and wasting effort on

Pro Tip: Prioritize based on outcomes, not the number of items completed. Focus on what moves the product closer to its vision.

Effective

- User needs

- Alignment with the roadmap

- Market demand

- Long-term sustainability

- Resource limits

- User impact

- Technical feasibility

- Urgency

Treating these as one checklist prevents any single voice from dominating and turns the

Ignore one force, and problems compound. Overweight user asks, and the team chases many small wins that do not advance objectives. Overweight

Pro Tip: Run the 3-question gate during grooming. If any answer is weak, hold the item and request evidence or estimates before it can move up.

A strategic

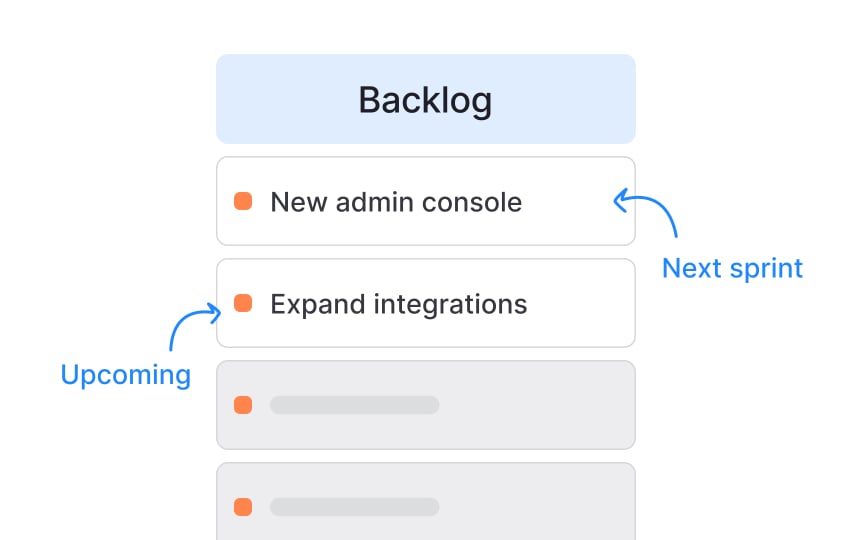

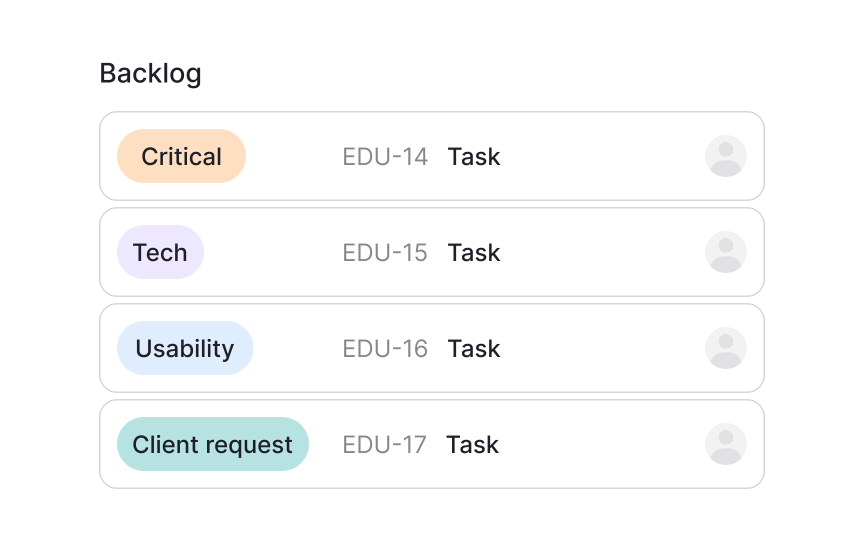

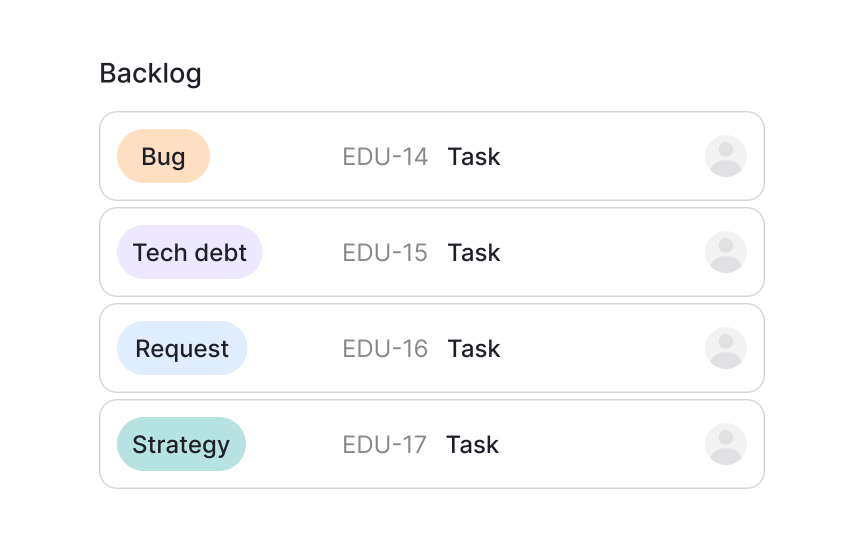

Everything below the cutoff belongs elsewhere. Create separate lists for longer-term ideas so the main backlog stays lean and credible. Add a simple bucketing system for the remaining items, for example, bugs, customer requests,

One risk of weak

The result is a roadmap that looks busy but lacks coherence. Features accumulate without a clear

A

- Bugs

Technical debt - Customer requests

- Strategic

initiatives

For example, a backlog may contain a critical login bug, a request from a long-term client for a custom report, a need to refactor an old API, and a strategic feature like real-time collaboration. Without categories, these items blend together, making it hard to judge what deserves attention first.

Categorization helps teams weigh trade-offs. Fixing the login bug prevents churn, addressing the API debt secures future scalability, and building real-time collaboration advances the roadmap vision. Customer requests remain visible but can be judged against strategic themes. This structure also supports sprint planning, where the team can decide to allocate part of the capacity to stability (bugs), part to long-term health (technical debt), and part to growth (strategic initiatives). Without it, the backlog risks becoming a black hole where urgent noise buries high-impact work. Structure transforms the backlog into a tool that directs attention toward meaningful outcomes.

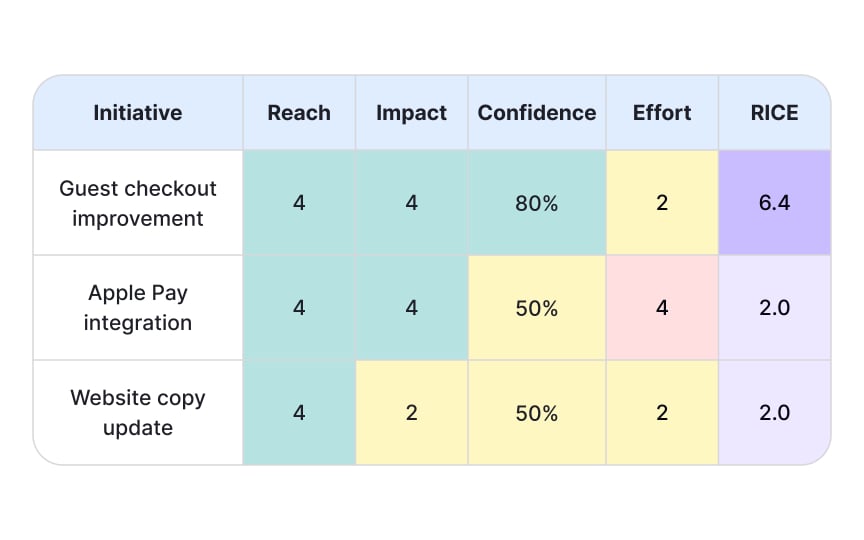

When priorities compete, intuition alone is not enough. Scoring systems introduce structure and make trade-offs visible. A common method is RICE, which multiplies reach, impact, and confidence, then divides by effort. Imagine two competing features: an improved search function and a new AI-powered recommendation engine. Search may have high reach and clear impact for all users but low effort. Recommendations may promise delight but come with high uncertainty and heavy engineering costs. Using RICE makes the difference transparent: search receives a stronger score, while recommendations can be scheduled later.

Weighted scoring models work in a similar way but allow teams to assign more importance to certain criteria, such as user experience or

When trade-offs are left unexplained, stakeholders often assume decisions are political or arbitrary. This erodes trust and invites repeated challenges. Transparency changes the conversation: people may not get the feature they want immediately, but they see how the choice advances agreed objectives. Communicating trade-offs also highlights the cost of changing priorities. Adding a feature for one large customer may delay roadmap items that improve the product for thousands. Making this impact explicit strengthens alignment and reduces conflict.

Saying “no” is one of the hardest but most important skills in

The key is context. A flat refusal frustrates stakeholders, but a “no” explained through goals and trade-offs builds credibility. For instance, declining a custom integration may be justified by showing how it would delay

Pro Tip: Revisit backlog priorities after each sprint. What mattered last cycle may no longer be the best investment today.

References

- 7 Ways to Prioritize Your Product Backlog | ProductPlan

Top contributors

Topics

From Course

Share

Similar lessons

What PMs Actually Do

The Frameworks that Guide You