The Frameworks that Guide You

Explore how to use proven frameworks to turn overwhelming ideas into clear priorities.

Ideas always come in greater numbers than a team can possibly deliver. Without structure, decisions often follow the loudest voice in the room rather than the initiatives that create real impact. Prioritization frameworks provide a consistent way to weigh competing demands, making choices clearer and easier to defend. They connect daily product work with long-term goals while keeping resources focused on what matters most.

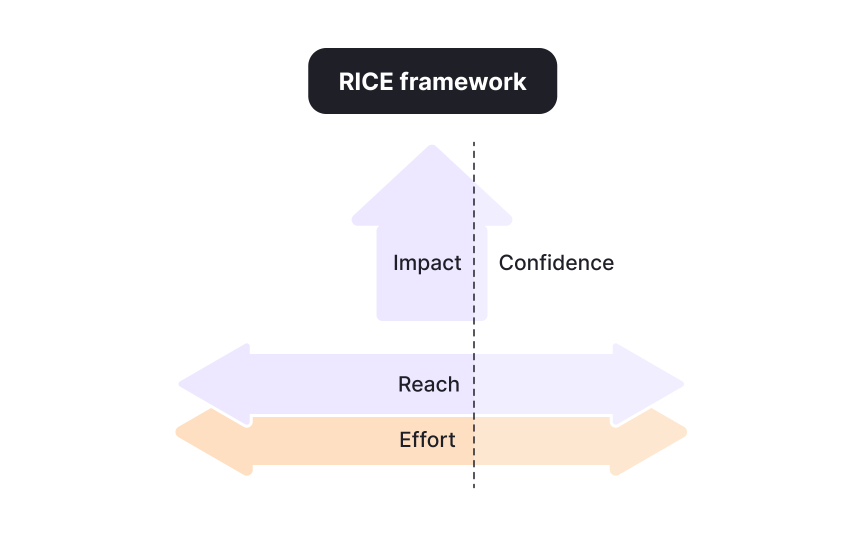

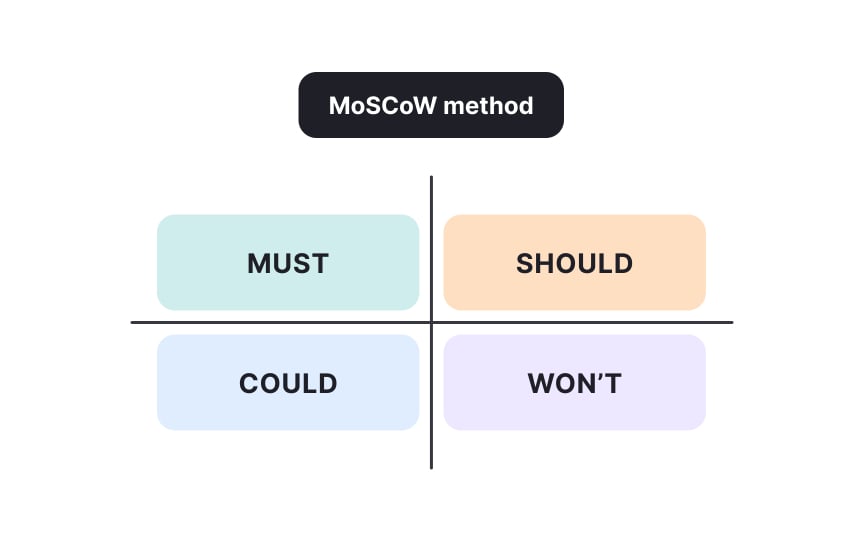

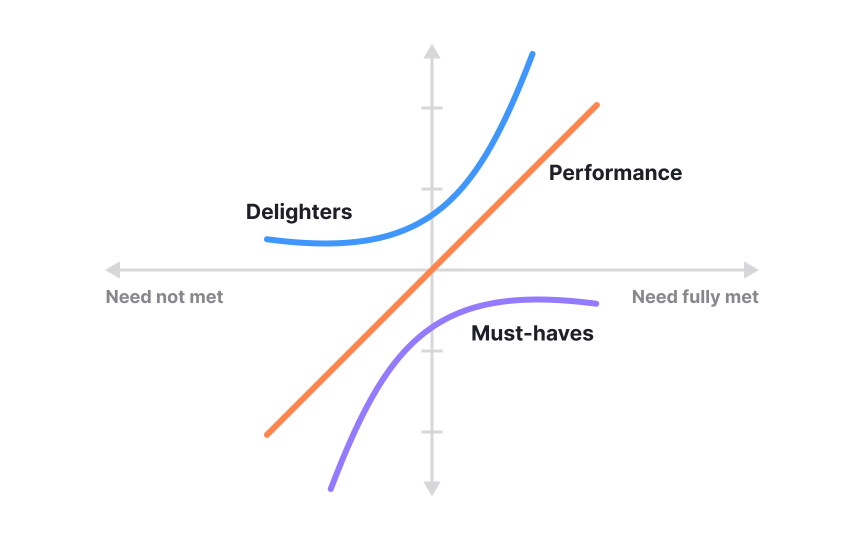

RICE brings numbers into the process by weighing reach, impact, confidence, and effort to calculate a score that highlights the strongest opportunities. MoSCoW sorts requirements into must, should, could, and won’t have, giving teams a shared language for scope and expectations. The Kano Model shifts attention to customer satisfaction, showing which features are essentials, which enhance performance, and which create delight.

Each method has its advantages and blind spots. RICE demands data and can feel heavy for fast decisions, MoSCoW is simple but sometimes too coarse, and Kano requires research that not every team can run. What unites them is their ability to replace gut feeling with structured reasoning. Choosing one framework that fits the culture of the company and applying it consistently turns prioritization into a shared practice rather than a recurring debate.

The RICE framework offers a structured way to compare product ideas that might otherwise compete only through intuition or stakeholder influence. It breaks evaluation into 4 factors:

- Reach estimates how many users or events will be affected during a defined period, such as active customers in a month or signups in a quarter.

- Impact measures the expected degree of change, for instance whether an idea will slightly improve a metric or strongly advance a strategic goal.

- Confidence reflects how certain the team is about the reach and impact estimates, usually expressed as high, medium, or low with percentages attached.

- Effort captures the resources needed to complete the

initiative , most often measured in person-months.

These factors are combined in a formula: reach × impact × confidence, divided by effort. The result is a RICE score that makes it possible to compare very different ideas on the same scale. Its value is not in absolute precision but in transparency. By forcing teams to write down their assumptions, it invites discussion about why an initiative is judged impactful or why confidence is low. This reduces hidden biases and creates a shared language for decision-making.

However, the framework also has drawbacks. Estimates can take time to gather and are prone to inconsistency if teams use different methods. A score can also look more reliable than it actually is. Despite these limits, RICE helps replace vague debates with structured reasoning, guiding teams toward priorities that balance ambition with feasibility.[1]

Once the RICE framework is understood in theory, the next step is to see how it works in practice. Imagine a team considering whether to build an onboarding tutorial for a new app. They estimate that the feature will reach about 5,000 new users per month. The impact is judged as medium, since it should improve activation but not directly affect revenue, giving it a value of 2 on a typical scale. The team feels reasonably confident about these estimates, rating confidence at 80 percent. The effort required is calculated at two person-months. When reach, impact, and confidence are multiplied together and divided by effort, the resulting

What makes this exercise powerful is not the number itself but the discussion it generates. Team members must explain why they believe onboarding will affect activation or why they are confident in the data. These conversations often reveal blind spots, such as overlooked dependencies or uncertain metrics. By applying RICE to a real case, even a simplified one, teams practice moving from intuition to structured reasoning. It also shows that RICE is not about eliminating judgment but about anchoring decisions in transparent criteria that can be reviewed and challenged.

Pro Tip: Focus on the reasoning behind each input, not just the final score. Numbers spark alignment when their meaning is clear.

The

- Must Have items are critical and define the foundation of the project. Without them, the product cannot succeed or even function.

- Should Have items are important but not indispensable. They may improve usability or efficiency, yet the release can move forward without them.

- Could Have items are optional additions. They might enhance user experience or create small advantages, but their absence will not damage the outcome.

- Won’t Have items are those explicitly excluded from the current scope, either because they are not feasible now or do not align with current objectives.

This clear categorization helps teams deal with limited time and resources. It forces alignment around what is truly necessary while still recognizing future possibilities. Another benefit is expectation management. By listing what will not be delivered, teams avoid misunderstandings with stakeholders.

The model’s simplicity, however, means it does not rank priorities within each category, which sometimes leads to further negotiation. Still, its ability to make scope explicit makes it a useful framework in projects where clarity and speed of decision-making are essential.[2]

Using

By framing decisions around one functionality, the categories become sharper and trade-offs more realistic. Teams can weigh technical complexity against user expectations without being overwhelmed by the entire scope of a product. This approach also highlights how MoSCoW manages expectations: stakeholders see clearly which improvements are non-negotiable and which are deferred. The simplicity of the method allows for quick alignment, while its main limitation remains the lack of

The

- Basic features (must-haves) are expected by users and, if absent, cause frustration. For example, in a messaging app, the ability to send text messages is a basic expectation.

- Performance features directly influence satisfaction in proportion to how well they are delivered. Faster load times or clearer video quality usually fit into this group.

- Delighters are unexpected extras that surprise users and create strong positive reactions, such as playful animations or creative personalization options.

Understanding this distinction prevents teams from overinvesting in features that add little perceived value while neglecting essentials. It also highlights the power of delight. A small but thoughtful addition can create lasting goodwill, even though its absence would not cause complaints. The challenge is that Kano analysis requires structured

The

For example, if most users say they “expect” a feature and “dislike” its absence, it is classified as a Basic. If satisfaction rises as the feature improves, it is a Performance. If many users say they “like it” when present but “don’t care” if absent, it is likely a Delighter.

Interpreting results requires careful grouping of responses. Teams can use discrete analysis, which categorizes answers into tables and counts the frequency of each feature type. A more advanced approach is continuous analysis, where each response is given a score on a satisfaction scale ranging from negative to positive values. This yields a more nuanced view of which features create delight and which risk frustration. By analyzing results in this way, product managers move beyond assumptions and gain a clear map of what customers value most, allowing

RICE,

- RICE is effective at quantifying trade-offs and creates defensible rankings that can be explained to stakeholders. Its drawback lies in the time and effort needed to gather reliable data and the risk of producing scores that appear precise but rest on uncertain assumptions.

- MoSCoW is easy to use and ensures clear communication with stakeholders by defining what must be delivered. However, it cannot rank items within categories, and disagreements about what qualifies as a Must Have can stall decisions.

- The Kano Model provides deep insights into customer perceptions, separating essentials from delighters. Yet it demands surveys, analysis, and customer samples, which may not always be practical.

Comparing the frameworks side by side helps highlight that the choice is not about finding the perfect system but about recognizing what best fits the team’s environment. Simplicity, data availability, and company culture all influence which framework works best. Each method creates structure and transparency, but their effectiveness depends on consistent application and awareness of their blind spots.

Pro Tip: Do not chase the “best” framework. Focus instead on which one your team can apply consistently and with confidence.

Selecting the right

- RICE works well when a team has access to reliable data and the capacity to invest time in estimates. It produces comparable scores and helps justify decisions, which can be useful in organizations where stakeholder alignment requires evidence.

- MoSCoW fits contexts where speed and clarity matter most. By defining what must and will not be delivered, it prevents scope creep and gives teams a common language for negotiation.

- The Kano Model is best suited when customer satisfaction is central to the product strategy and the team is able to conduct surveys or interviews that reveal how users truly perceive features.

The decision should also consider the maturity of the organization. New teams may find RICE too heavy and benefit more from

Introducing a framework is only the first step. Its value emerges when teams commit to using it consistently, even when debates are intense or deadlines are pressing. Switching between methods or applying them selectively can create confusion and weaken trust in the process. For example, if a team uses RICE for some decisions but reverts to intuition when results are inconvenient, the framework loses credibility. Commitment means applying the chosen method to all

Consistency also builds shared understanding. Over time, stakeholders become familiar with the framework’s language, whether it is Must Have or Delighter, and this reduces friction in discussions. Regular reviews ensure the framework stays relevant, since priorities evolve with the market and the product. Committing does not mean rigidity. It means using the framework as the baseline for structured decisions, while allowing space for thoughtful adjustments when evidence justifies them. This balance of discipline and flexibility ensures that

References

- MoSCoW Prioritization Model | ProdPad | ProdPad

- How to Use the Kano Model to Prioritize Features | ProductPlan

Topics

From Course

Share

Similar lessons

What PMs Actually Do

The Art of Prioritization