MVP Design

Design lean, testable MVPs that validate core value with minimal effort and maximum insight.

As you complete your product strategy, you now transition from defining what the product should achieve to how to start validating those strategic choices effectively. The MVP is the practical embodiment of your strategy. It is a focused experiment designed to test your core assumptions with minimal investment.

Building a minimum viable product is like creating the first architectural model before constructing a building. The model is not the finished structure, but it reveals whether the design makes sense, whether the layout works, and whether people can imagine living or working in that space. Instead of pouring resources into a full build, the team focuses on testing the essentials and gathering feedback early.

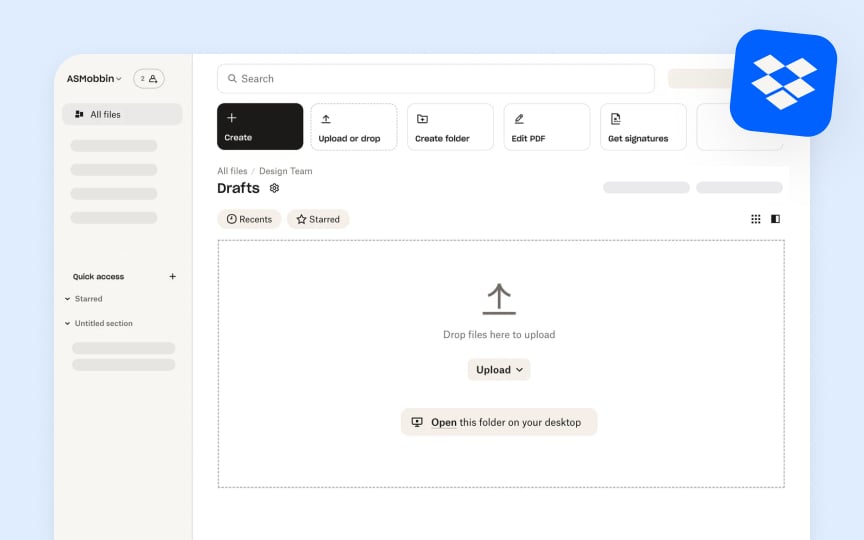

An MVP is not a rough prototype or a half-built feature set. It is a working solution that does just enough to test a clear assumption. Think of the early days of Dropbox, when the team used a simple video demo to show how file syncing could work. That minimal step gave them thousands of sign-ups before they wrote most of the code. Such examples show how MVPs help reduce risks, validate demand, and avoid investing years into building something nobody needs.[1]

By treating MVPs as focused experiments rather than cut-down products, teams create space to learn, adapt, and steadily move closer to solutions that both users and businesses value.

MVPs, prototypes, and beta releases often get confused, yet they serve different roles in product development. Understanding these differences helps teams design with purpose.

A

The

Pro Tip: Remember: prototypes test ideas, MVPs test value, and betas test stability.

While earlier research helped identify various market gaps and user pain points,

Early research also prevents teams from wasting effort on features that look appealing but are not actually useful. Insights like these shape the MVP into a solution that fits real behavior.

The value of research lies not in collecting endless data but in identifying patterns that highlight genuine needs. With this focus, the MVP becomes a test of something meaningful, not a shot in the dark.

The first step in designing an

To identify the right focus, teams should rely on user research and observed pain points. Prioritize the issues that appear most frequently or cause the greatest frustration. For example, if many users struggle to manage invoices, the main challenge may not be adding more accounting features, but simplifying how they follow rules and handle taxes. Addressing one critical pain point creates a strong foundation for iteration and expansion later.[3]

A clear and specific problem statement keeps all stakeholders aligned. Designers, developers, and managers need to agree on the same challenge to avoid confusion and misdirected effort. Writing it down ensures the MVP becomes an intentional experiment aimed at solving a real user problem, not a collection of assumptions.[4]

Pro Tip: Write the MVP problem in one sentence. If it feels vague or too broad, narrow it until it describes one clear challenge.

An

Success should always be measurable. A vague statement like “users should enjoy the product” is not enough, because enjoyment cannot be tracked in a precise way. A better criterion is “at least 60% of test users should complete a purchase flow without errors.” The difference is that one can be measured, compared, and used to guide the next step, while the other is open to guesswork.

Good criteria often focus on user behavior, adoption rates, or usability scores. These benchmarks prevent wasted effort, as they give a clear signal of whether the MVP meets expectations. They also build trust with stakeholders, since everyone knows what evidence will guide decisions about refining, pivoting, or investing further.[5]

Pro Tip: Replace vague goals like “users like it” with measurable ones, such as “50% return to use it again within a week.”

An

A poor value proposition might say, “A tool for better teamwork,” which is vague and hard to measure. A clearer one would be, “A tool that lets remote teams share files instantly and reduce email use by 40%.” The second example is more specific and makes a promise that can be tested.

By formulating the value proposition early, the team gains a reference point for feature selection and evaluation. If a proposed feature does not support the promise, it likely does not belong in the MVP. This discipline keeps the design simple and aligned with the problem.

Pro Tip: If your value proposition cannot be explained in under 30 seconds, refine it until it is clear and specific.

A common mistake in

The must-haves are the ones directly linked to the problem and

Prioritization prevents wasted resources and shortens development time. It also makes testing clearer, because users can focus on the essential function. The art of MVP design is not in how much is included, but in how much is left out.

Pro Tip: Ask of each feature: does this solve the main problem? If not, move it to the later list.

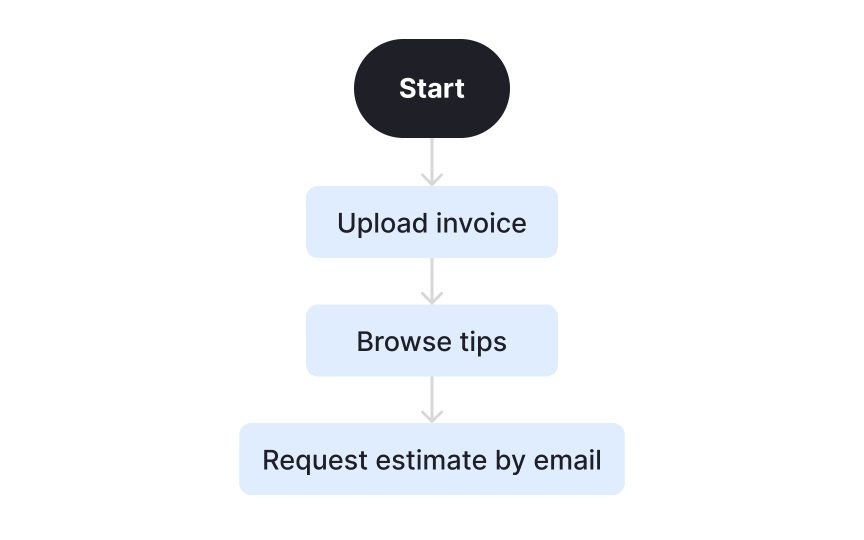

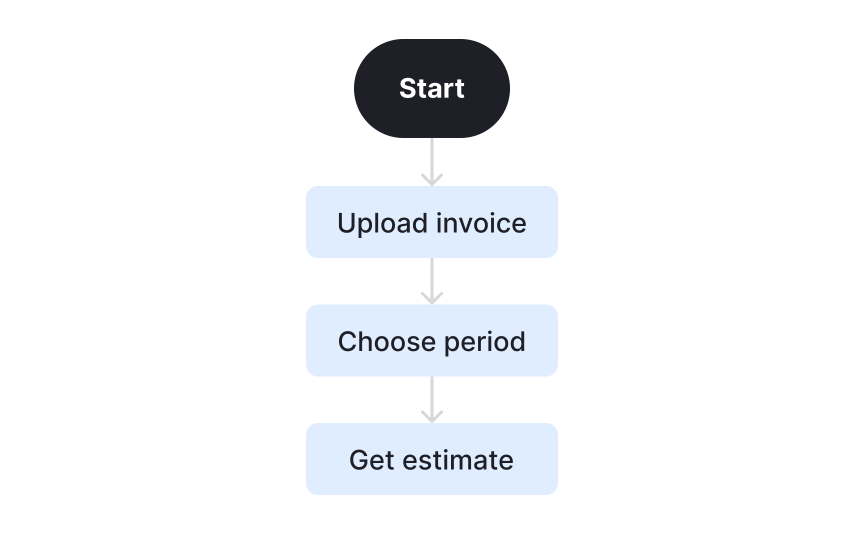

User flows show the exact steps people take to complete a task inside a product. For an

When mapping, the focus should stay on the primary tasks connected to the MVP’s problem. For example, if the MVP is a tax calculator add-on, the flow might start with uploading an invoice, continue with selecting a period, and end with receiving a calculation. Secondary paths, such as exporting data to other tools, can be left aside until later.

By creating and testing user flows early, teams can identify unnecessary steps, remove confusion, and guide design choices. This visual approach also helps everyone on the team see the same picture of what matters most in the first release.

Pro Tip: Draw only the steps needed to finish the core task. Extra paths can be added once the MVP proves its value.

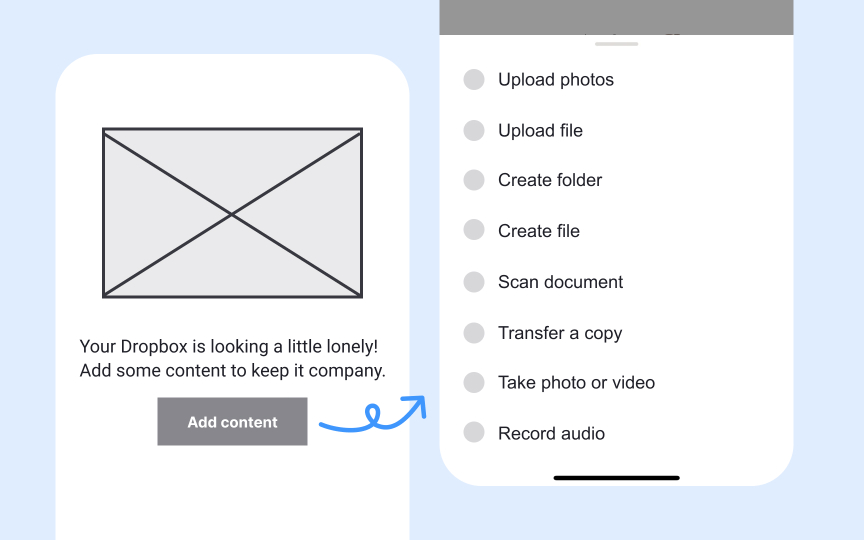

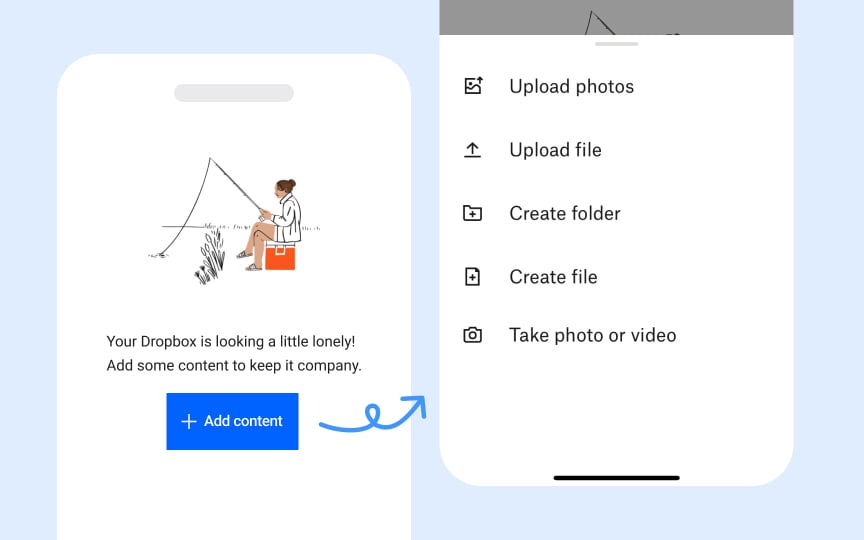

Most MVPs begin with low-fidelity wireframes or simple

Because the goal at this stage is validation, clarity matters more than polish. Even a simple sketch can reveal whether users understand where to click or how to complete a task. For example, a wireframe for a file-sharing

High-fidelity prototypes with full color, branding, and realistic UI elements are typically developed later, once the MVP shows signs of product–market fit or when usability testing expands to a broader audience. Creating these detailed assets too early is costly and risky because they assume user preferences that have not yet been validated. Starting with lo-fi designs allows teams to learn quickly, adjust easily, and invest in polish only once the essentials are proven.

Tests can involve simple scenarios, such as asking participants to upload a file or complete a checkout. Observing how they navigate shows whether the flow is clear. If users get lost or misinterpret

Running usability tests before launch saves time and resources. It allows the team to fix issues early rather than after scaling. This practice ensures that the MVP measures value, not confusion caused by poor design.

Pro Tip: Watch where users hesitate during tests. Those pauses often reveal where improvements are needed.

The work does not end once an

Metrics such as completion rates, sign-ups, or satisfaction scores highlight where the product succeeds and where it falls short. Iterative testing frameworks encourage small, focused changes rather than large redesigns. For example, if users consistently fail at one step in the flow, a targeted fix is more effective than overhauling the entire interface.

This cycle creates a rhythm of learning and improvement. Each version moves the MVP closer to meeting real needs while avoiding wasted effort. Instead of guessing, teams rely on data and user voices to shape the path forward.

References

- The ORIGINAL Dropbox MVP Explainer Video | Shortform Books

- Prototype Testing in Software Testing - GeeksforGeeks | GeeksforGeeks

- Design Thinking | Design Thinking

- Guide to Writing an Effective Problem Statement | ProductPlan

Topics

From Course

Images provided by

Share

Similar lessons

10 Usability Heuristics by Jakob Nielsen

Usability Heuristics