Opportunity Ideation

Master ideation techniques to generate creative product ideas and spot real market opportunities.

People rarely buy a product for its features alone. They buy it because it solves a problem or fulfills a need. Ideation is the stage where product teams generate a wide range of possible solutions before narrowing down to the most promising ones. This process combines creativity with structure, enabling teams to move beyond surface-level ideas and uncover opportunities that can set their product apart.

Ideation can be sparked by observing gaps in the market or by exploring a hunch about unmet user needs. It thrives on collaboration, where diverse perspectives bring new insights to the table. Structured methods such as brainstorming, brainwriting, SCAMPER, and even deliberately creating the “worst possible idea” help push thinking beyond the obvious. These techniques reduce biases, encourage equal participation, and unlock unexpected directions.

The ultimate aim of ideation is not to land on a single perfect idea but to expand the range of possibilities. Once these ideas are shared and refined, the team can evaluate which ones align best with user needs, competitive advantages, and business goals. A strong ideation process lays the foundation for effective concept testing and eventual product development.

Ideation is a defined stage in the product development process where teams purposefully generate many possible solutions before any building begins. Ideas can be triggered by observed gaps in the market or by a promising hunch worth early exploration. The goal here is to open options, not to prove a single answer.

A structured ideation session brings cross-functional people together to surface diverse perspectives on a problem. Facilitators frame the challenge, timebox rounds, and capture every idea without judging quality. This divergent step reduces bias and groupthink, increases participation, and prevents a premature commitment to one direction.

Ideation produces a broad set of candidate concepts to review against user needs, business goals, and technical limits. These concepts feed the next stages, such as early research, prototyping, and testing. Treating ideation as a distinct phase builds a shared language and lowers risk by separating creative exploration from evaluation.[1]

Pro Tip: State the challenge, set a short timer, and capture every idea without judging. Divergence first, evaluation later.

Market gaps are unmet needs that appear when existing products do not fully solve a problem. Teams can surface these gaps through competitive analysis that covers direct competitors with the same job and indirect competitors with alternative approaches. Mapping the landscape shows where others are strong, where they fall short, and where demand remains open.

Select a focused competitor set, then compare offerings across features, pricing, usability, and messaging. Public sources like websites, app stores, and support forums reveal complaints, workarounds, and ignored user groups. These signals point to opportunities grounded in evidence, not opinion.

This exercise fits flexibly into the

Bring findings into ideation as prompts. Phrase each gap as a problem statement linking a user, a task, and a barrier. Use these statements to steer idea generation and avoid chasing concepts that lack market relevance. When ideas start from documented gaps, teams are more likely to craft solutions that feel valuable and testable next.[2]

Pro Tip: Write gaps as “For [user], doing [task] is blocked by [barrier]” and use each as an ideation prompt.

Collaboration in ideation works best when it is guided so that every voice is heard. Different roles bring unique perspectives, but without structure, discussions can wander or be led by a few dominant speakers. A good session starts with a clear problem statement written in simple words so that everyone understands the challenge in the same way.

To make collaboration practical, use techniques that balance contributions. One useful approach is to ask each participant to share one idea in turn before any group discussion. This ensures quieter members contribute equally. A shared space, such as a whiteboard or an online board, helps record ideas visibly so others can add or adapt them. Mixing people from design, engineering, and business roles can spark new connections, such as a technical suggestion improving a creative sketch. This kind of collaboration not only produces richer ideas but also builds a sense of shared ownership and trust across the team.

To make brainstorming sessions effective, the facilitator should prepare a clear problem statement and set a short time limit to keep energy high. Recording every idea on sticky notes or in a digital tool ensures that nothing is forgotten. Encouraging participants to build on each other’s contributions often leads to stronger results than isolated thinking. Once the session ends, the group can cluster ideas into themes and decide which ones are worth testing further. Structured in this way, brainstorming becomes a fast and inclusive tool for early ideation.

Brainwriting is a structured alternative to

The benefit of brainwriting lies in both quantity and diversity. Because people see and build on each other’s notes, the group often generates more varied and unexpected concepts than they would through conversation alone. It also prevents groupthink, since everyone contributes independently before seeing others’ thoughts. Over time, teams discover ideas that might not have emerged in traditional meetings, making brainwriting particularly useful for early ideation stages where openness is more valuable than refinement.[3]

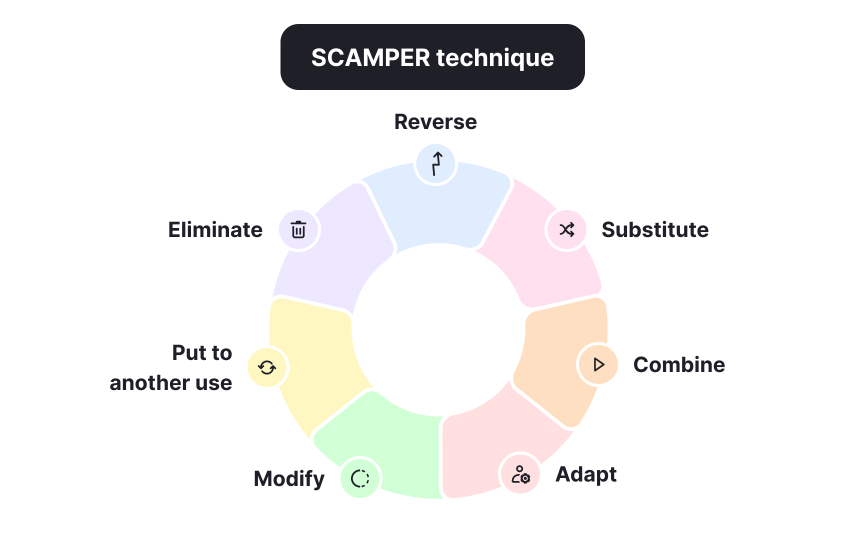

SCAMPER is a framework that helps teams create new ideas by asking 7 types of questions about existing products and services. Instead of waiting for inspiration, it gives a method to look at things differently and spark innovation. The goal is not always to invent something completely new, but to see how changes can add value, improve

- Substitute means replacing one part with another. Paper tickets, for example, were substituted with QR codes.

- Combine is about merging functions, such as smartphones that joined cameras, music players, and phones in one device.

- Adapt means changing something for a new use, like Netflix adapting its DVD rental model into streaming.[4]

- Modify focuses on altering size, shape, or emphasis, such as Instagram making Stories highly visible by putting them at the top of the app.

- Put to Another Use takes what already exists and applies it elsewhere. Adidas made shoes from ocean plastics, showing how waste materials could gain new life.[5]

- Eliminate simplifies a product by removing parts that are no longer needed, like Bluetooth headphones removing wires.

- Reverse flips the usual way of doing things, such as subscriptions replacing one-time purchases.[6]

By moving through these 7 steps, teams can discover fresh ideas, avoid getting stuck, and challenge the habits that keep products from improving.

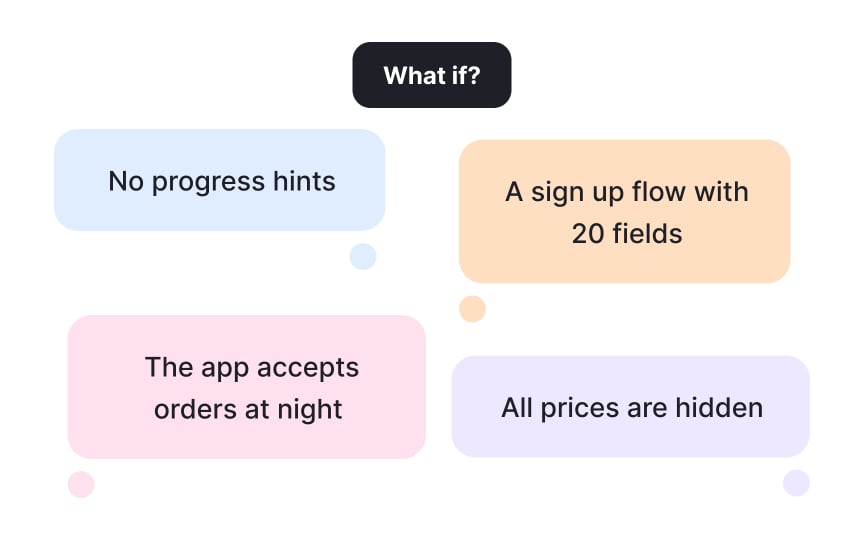

The Worst Possible Idea technique invites teams to deliberately generate absurd or clearly bad ideas. By doing this on purpose, the group lowers the fear of being wrong and breaks free from routine thinking. Because it feels easier to think of poor solutions than good ones, the method is also useful when a team faces a creative block. Listing “bad” ideas can loosen up thinking and often leads to stronger “good” ideas right after.

To use WPI, begin with a short and specific question, such as “How can we improve the checkout flow?” Set a timer and ask everyone to suggest the most unhelpful designs they can imagine. For example, a sign-up form with 20 required fields and no progress indicator highlights the opposite of what users need: speed and guidance. A food delivery app that only works at night shows why availability is essential. An online shop that hides

The final step is to flip each worst idea into a positive design rule or hypothesis. The 20-field form becomes “request the fewest inputs and show progress cues.” The night-only service becomes “offer clear hours and reliable coverage.” The hidden prices become “show totals early.” Summarize these lessons as simple do and do not rules that can guide sketches, storyboards, or quick

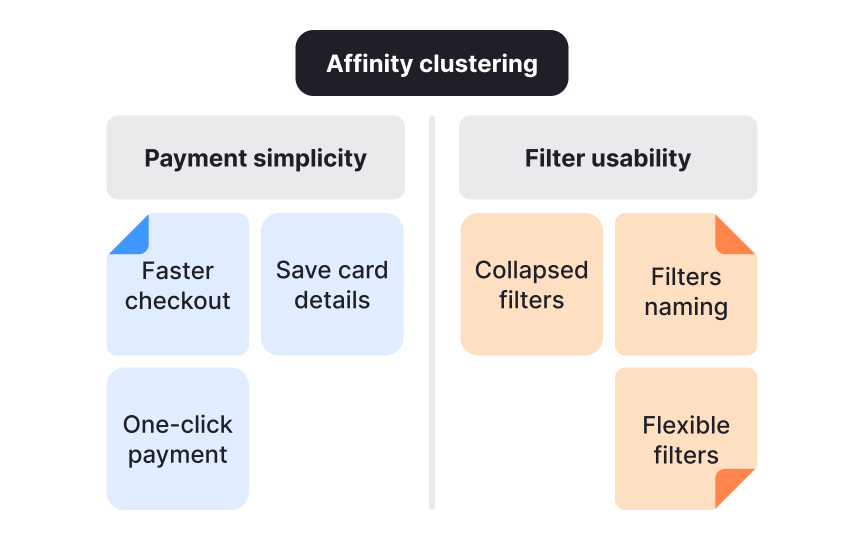

When ideation sessions generate dozens of suggestions, their value depends on how well those ideas are captured. Writing everything down ensures no contribution is lost, even if it looks impractical at first. Teams often use sticky notes, whiteboards, or digital boards to log each idea in a short, clear phrase. Recording ideas in this way creates a shared memory that prevents dominant voices from deciding which suggestions “deserve” attention.

The next step is clustering. Similar or related ideas are grouped together to reveal emerging themes. For example, in a session about improving an online shop, notes like “faster

Pro Tip: Always cluster before prioritizing. Otherwise, strong individual ideas may overshadow themes that represent deeper opportunities.

Once ideas are documented, the next step is to test how closely they match real user needs. A concept may seem smart or innovative, but if it does not solve a problem users care about, it is unlikely to succeed. This is why evaluation should be grounded in

The most reliable evaluations use simple, consistent criteria. For instance, a mobile banking team could ask: does this feature save users time, lower their stress, or build trust? A feature such as “instant spending alerts” clearly aligns with these needs, while an idea like “animated login screens” might entertain without adding real value. Linking each idea to a job to be done keeps the review structured and prevents the team from being distracted by novelty. By anchoring selection in evidence, the team channels effort toward ideas with measurable impact.

Pro Tip: Translate each user need into a “job to be done” statement, then check every idea against it.

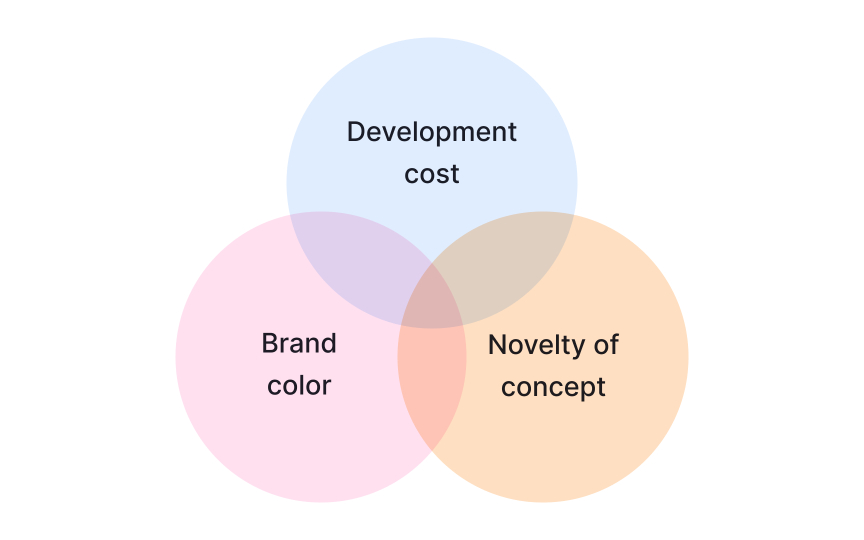

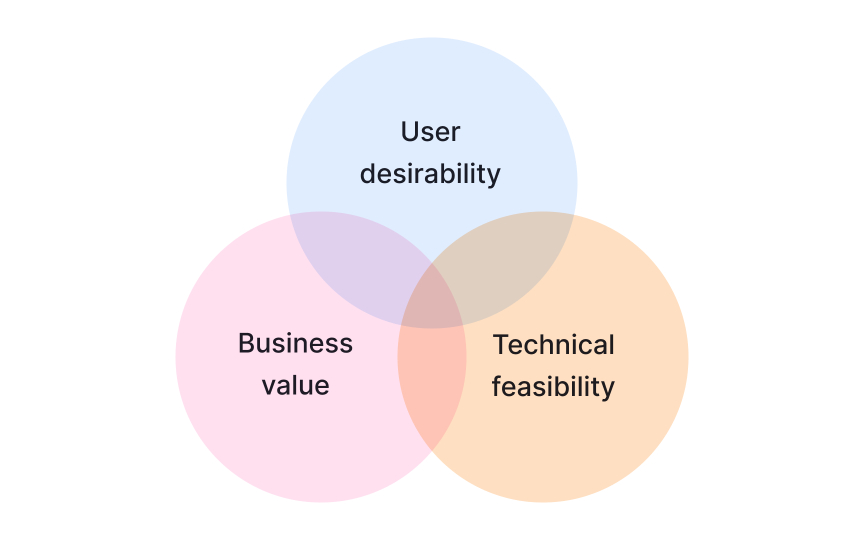

After filtering ideas through user needs, the next challenge is to choose which ones should advance to concept testing. This is not about finding the single perfect idea but about building a shortlist of promising candidates that deserve closer investigation. Teams often apply 3 guiding lenses:

- User desirability

- Business value

- Technical feasibility

Looking at ideas through these perspectives ensures balance between what customers want, what benefits the business, and what is practical to deliver.

A scoring model can make this process more transparent. Each idea is rated across the 3 lenses, and the results are compared. For example, a “simplified

References

- What is Brainwriting? | Miro | https://miro.com/

- What is Worst Possible Idea? — updated 2025 | The Interaction Design Foundation

Topics

From Course

Share

Similar lessons

Product Development Lifecycle

Product Development Stages