Product Definition

Define the product’s value and set clear measures of success from the start.

Defining a product is more than shaping features. It means clarifying the value it delivers and deciding how success will be measured. Without this foundation, even strong ideas risk losing direction once they enter development.

The value proposition is the first anchor. It explains the problem the product is built to solve and why it matters more than existing alternatives. It becomes a guide for research, design, and marketing by showing what makes the product different and relevant.

Equally important are success metrics. These provide a concrete way to evaluate progress once the product launches. Metrics can be broad, like revenue or customer retention, or targeted, like average order value or daily active users. Choosing the right ones early keeps teams aligned and prevents misjudging performance later.

Together, a clear value proposition and well-defined metrics turn vague ideas into structured products. They help teams make evidence-based decisions, communicate consistently, and stay focused on both user needs and business goals.

A

Strong propositions describe users’ challenges, outline the improvement offered, and highlight how the product differs from alternatives. Stripe illustrates this well with its statement, “Financial infrastructure to grow your

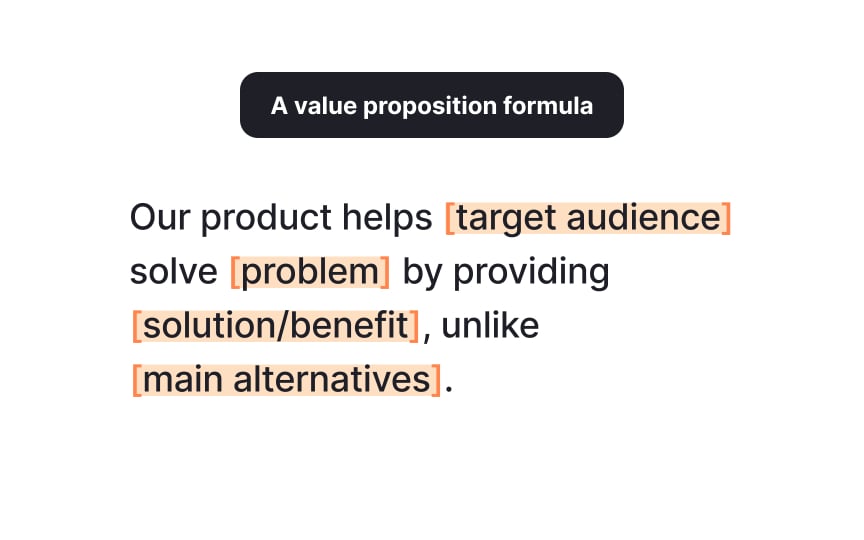

To create such clarity, many experts recommend following a simple formula: “Our product helps [target audience] solve [problem] by providing [solution/benefit], unlike [main alternatives].” This format ensures that the statement answers what the product does, who it serves, and why it is unique. If an outsider can restate the benefit in their own words after reading it once, the proposition is strong enough to guide development.[1]

Pro Tip: Collect 5 user complaints and reframe each into a “we solve X by Y” sentence.

A strong

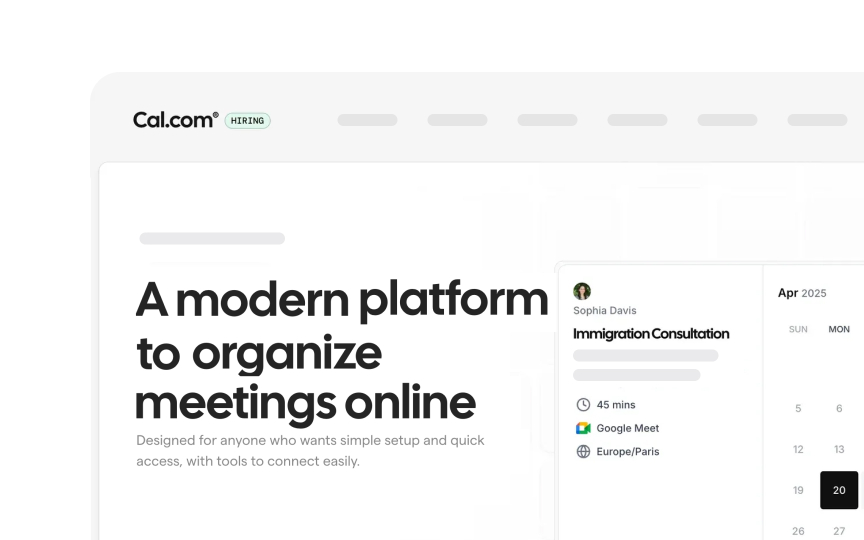

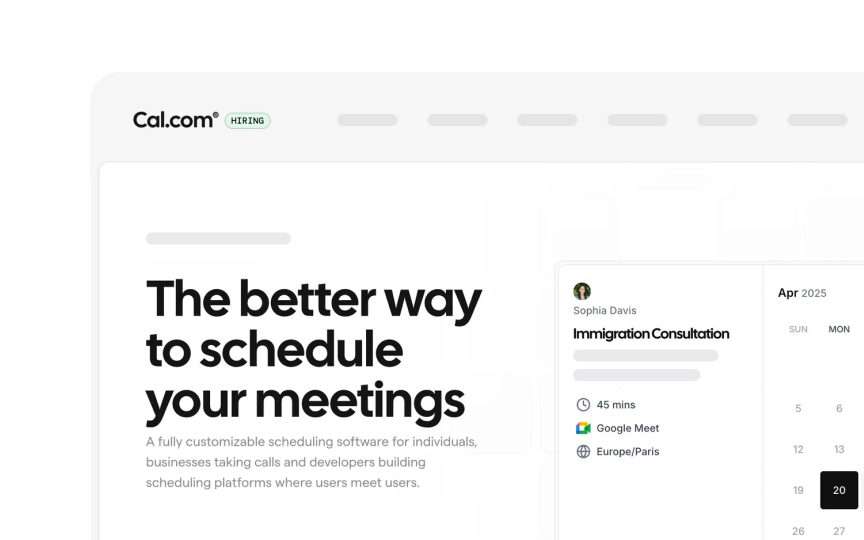

For example, scheduling meetings across teams often creates confusion and wasted time because people use different calendars, time zones, and tools, leading to endless back-and-forth messages. Cal.com translates this pain into a promise by positioning itself as a customizable scheduling platform that makes coordination easier for individuals, businesses, and developers. The benefit is not just another tool but a better, more flexible way to manage appointments.

Teams take the captured user pain points they gathered in the Discovery and Validation phase and then create a table with 2 columns: one for the specific pain and one for the product’s promise in response. This structured translation ensures that the value proposition is not abstract but directly linked to the problems users most want solved.

Pro Tip: Ask users to rank their top 3 pains and solve the one that appears most often first.

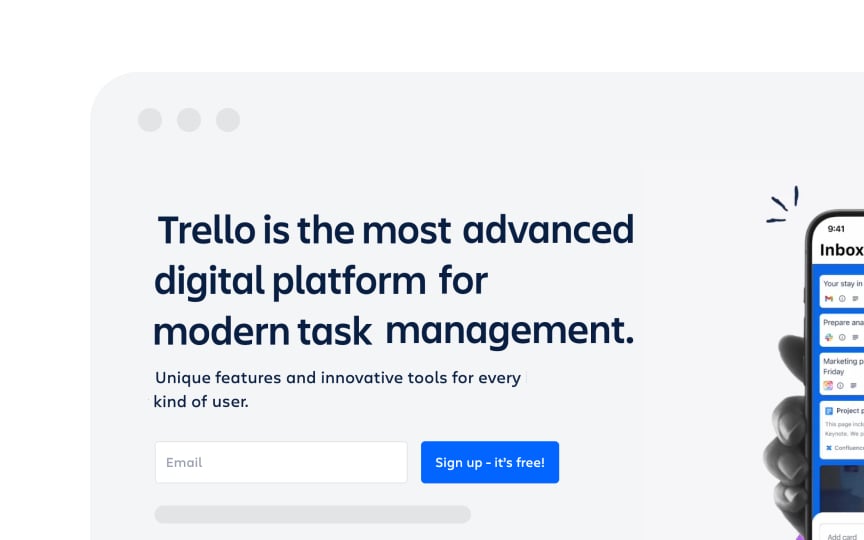

The gap between strong and weak value propositions becomes very clear when comparing statements on the same topic. Weak ones often use generic or exaggerated wording that could fit almost any product. Imagine a task-management tool promoted with a phrase like “The world’s most advanced digital experience.” While it sounds impressive, it fails to explain what the tool does or why anyone should use it.

By contrast, Trello communicates its usefulness by focusing on practical benefits such as capturing tasks, organizing them, and enabling teamwork from anywhere. This makes the value immediately relevant and easy to understand.

Strong propositions are short, specific, and customer-centered, while weak ones hide behind buzzwords or inflated claims.

A strong

To test whether a value proposition works, gather a small group of people who are not familiar with the product. Share the statement with them and ask what they think the product does, who it is for, and what outcome it delivers. If their answers match your intent, the proposition is clear. If not, it needs refining.

Defining a product becomes clearer when you examine how competitors express their value. By comparing value propositions side by side, you can see not just what others offer but also how they choose to present it. For example, in meetings and communication, Google Meet emphasizes accessibility by promising that anyone can join calls and collaborate from anywhere. Its message is simplicity and universality, appealing to both casual and professional users. A competitor in the same space might highlight customization or developer integration, showing its strength in flexibility rather than broad accessibility. Both address the same need but position themselves differently.

At the product definition stage, competitor positions should already be well understood from earlier discovery work. The goal here is to use that knowledge to sharpen your own message. A

To practice, select 3 competitors in a market, write down their public value statements, and compare how each answers the questions:

- What the product offers

- Who it helps

- What outcome it enables

The aim is to write it in a way that highlights what makes your product distinctive while still being clear, specific, and customer-focused.

A product pitch often begins as a broad promise, but to serve as a

For instance, instead of saying that a tool helps teams save time, the statement could specify that it reduces the average time to schedule a meeting from hours to minutes or lowers the number of missed calls by a clear percentage. Framing benefits in measurable terms makes the proposition more credible and easier to test later with real data.

To practice, take a draft product pitch and rewrite it by adding numbers that reflect efficiency, cost savings, or user satisfaction. This not only strengthens the message but also sets up clear expectations that can later be validated through success metrics.[2]

Not all metrics reflect meaningful progress. Vanity metrics often look impressive but give little clarity on whether a product is succeeding. These can be raw counts like total downloads or total registered users. Such numbers may rise quickly, yet they do not show whether people actually find value in the product. They can create a false sense of success because they are easy to measure but lack long-term insight.

Actionable Metrics, on the other hand, are tied directly to decisions that improve product outcomes. They indicate whether users return, whether the business model is sustainable, and whether the product addresses ongoing needs. Examples include customer retention rate, recurring

To practice, review a list of potential metrics and decide which are vanity and which are actionable. This distinction keeps teams focused on growth that drives lasting value, rather than chasing numbers that only look good on paper.[4]

Success metrics are most useful when they are tied directly to how users interact with a product. Numbers that show

By connecting metrics to behavior, teams can uncover why a product is succeeding or struggling. A rise in churn, for example, may signal that users find onboarding confusing or that the

To practice, choose one key business metric, such as

Pro Tip: Pair each metric with at least one observed behavior and avoid tracking them in isolation.

While many behaviors and outcomes can be measured, it is crucial to pick a focused set of KPIs that truly reflect your product’s core objectives and company strategy.

Early in product development, it is tempting to measure everything, but choosing a few focused key performance indicators (KPIs) creates stronger alignment. These KPIs should reflect the company’s priorities rather than surface activity. For example, a subscription business may focus on recurring

For product managers who are not yet familiar with metrics, a practical starting point is reviewing established guides. These resources list common metrics across areas like sales,

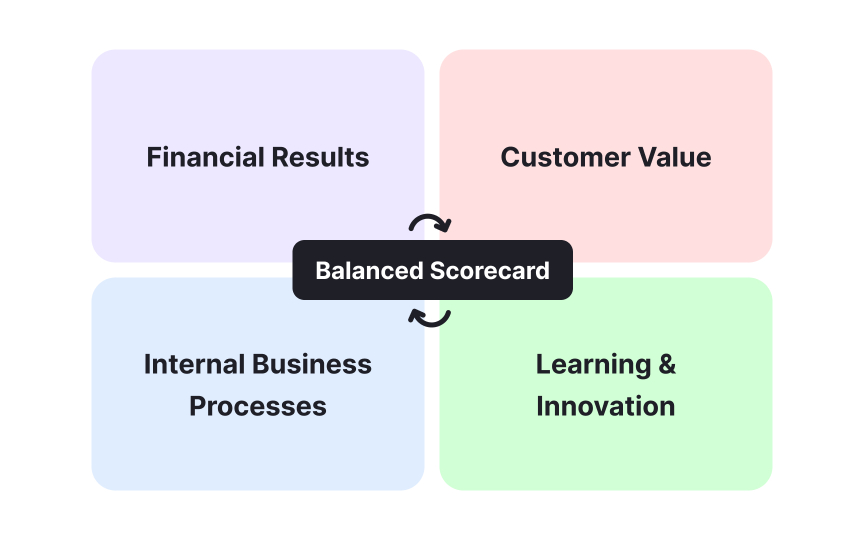

The balanced scorecard, introduced by Kaplan and Norton, is a framework for measuring performance from 4 perspectives:

- Financial results

- Customer value

- Internal business processes

- Learning or innovation

Unlike traditional approaches that focus mainly on

To apply it, start by identifying one goal for each perspective. A financial goal might be reaching a revenue target, while a customer goal could involve achieving a high satisfaction score. Internal process goals may include reducing support response time, and learning goals could focus on developing new release capabilities.

Assign a specific metric to each goal. This structure ensures that product teams balance immediate performance with future growth and resilience.[5]

Pro Tip: Before approving a new feature, check if it advances at least one scorecard perspective.

References

- The Balanced Scorecard—Measures that Drive Performance | Harvard Business Review

Topics

From Course

Share

Similar lessons

Introduction to Churn Metrics and Analysis

Common Causes of Customer Churn