Navigating Trade-offs and Dependencies

Balance competing priorities and manage dependencies to keep products moving forward.

Trade-offs and dependencies shape every stage of product development. No team has unlimited time or resources, which makes it necessary to choose between competing priorities. Each decision creates opportunity costs and impacts design, technical feasibility, and business outcomes. Recognizing these trade-offs is essential for steering a product toward long-term value instead of short-term wins.

Dependencies add another layer of complexity. Features often rely on other tasks, teams, or external partners, and delays in one area can ripple through the entire roadmap. Clear identification, mapping, and management of these relationships help reduce risk and keep initiatives aligned with strategic goals.

Understanding how to weigh trade-offs and manage dependencies builds confidence in decision-making. It gives teams a shared framework for prioritizing, reduces uncertainty, and keeps progress steady even when constraints are unavoidable.

Product management is often described as the art of trade-offs because very few decisions are free of downsides. Choosing to build one feature means postponing or abandoning another. A feature that seems like the obvious choice still consumes time, money, or focus that could have gone elsewhere. Good product managers make these limitations visible instead of hiding them. They explain both the strengths of a chosen path and the weaknesses it creates. This habit builds credibility with stakeholders, as it shows that decisions are not made blindly but after weighing different scenarios.

Trade-offs also help teams connect their work to opportunity costs. By asking what is lost when choosing one

Pro Tip: Highlight both the benefits and drawbacks of a choice to show clarity in reasoning.

Trade-offs and dependencies often appear together in product work, but they are not the same:

- A trade-off is a choice between competing options, where gaining one benefit means giving up another. For example, delivering a feature quickly may improve time-to-market but reduce design quality. Trade-offs are unavoidable because resources like time and budget are limited.

- A dependency, on the other hand, is when one task or outcome relies on another. For instance, testing cannot begin until development is complete.

Dependencies are about sequencing and coordination, while trade-offs are about conscious choices between alternatives.

Making this distinction clear prevents confusion. Trade-offs are shaped by constraints and opportunity costs, while dependencies highlight relationships that can slow or enable progress. Product managers must recognize both to manage risks effectively and to explain why decisions or delays occur.

Opportunity cost is a specific kind of trade-off that comes from limited resources. It describes the value that is sacrificed when one option is chosen over another. In

Recognizing opportunity costs pushes teams to ask, “What are we giving up if we pursue this?” This question helps expose hidden consequences and prevents decisions from being evaluated in isolation. Product managers who use this lens avoid narrow thinking. They connect short-term wins with potential long-term costs, such as added maintenance or reduced flexibility. Framing decisions with opportunity costs also supports alignment. It allows stakeholders to see not only what is being delivered but also what is consciously postponed.[2]

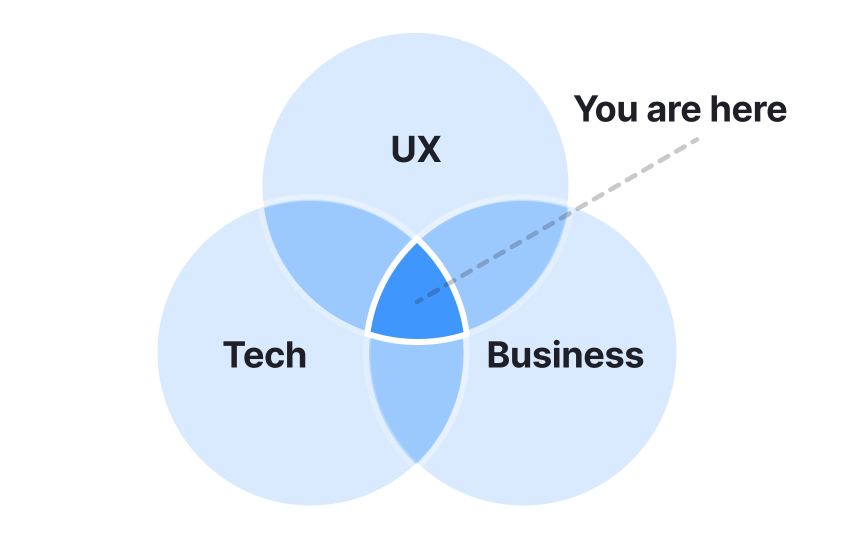

Every product decision involves balancing the interests of different perspectives. On one side are users, who expect solutions that ease pain points or improve their experience. On another side are business leaders, who need outcomes that support revenue, growth, or compliance. The third side belongs to engineers, who must ensure that solutions are technically feasible, scalable, and maintainable. Each group brings valid priorities, but leaning too heavily toward one risks undermining the others.

Trade-offs highlight where tensions appear. For example, improving personalization may increase user satisfaction but raise privacy concerns and technical complexity. Similarly, targeting a new market can unlock revenue but stretch development resources. Product managers are expected to articulate these trade-offs clearly, showing how user value, business outcomes, and technical effort are weighed together. This balance makes decisions credible and prevents them from being interpreted as biased toward one discipline.

Trade-offs in

- Technical versus design

- Technical versus business

- Business versus technical

- Business versus design

- Design versus technical

- Design versus business

Each combination represents a tension point where teams must make choices about what to prioritize.

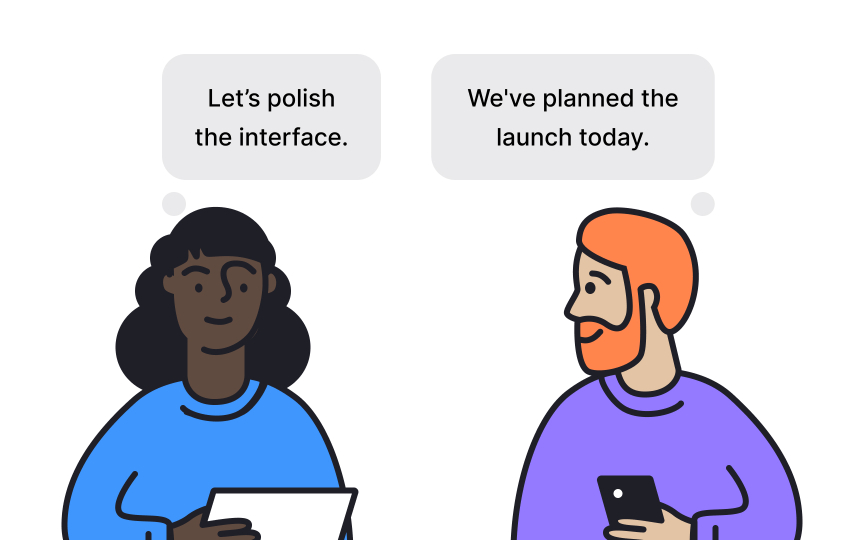

For example, technical versus design may require choosing between a simple but less appealing solution and a more polished interface that adds complexity. Business versus design might involve speeding up delivery to capture

Pro Tip: Use trade-off categories to clarify tensions and reveal what is being sacrificed in each decision.

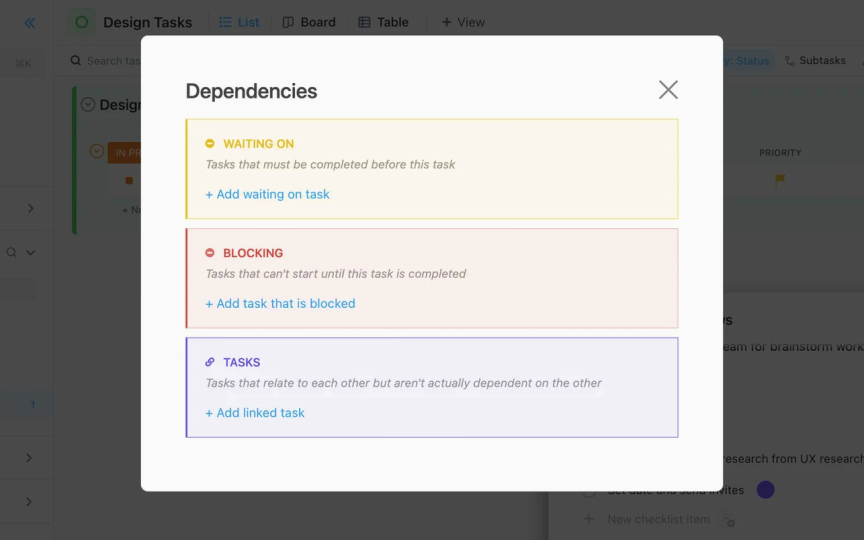

Dependencies describe how tasks or

Others are external, lying outside the team’s direct influence. These often involve other departments, partners, or third parties. Examples include waiting for legal approval, vendor deliveries, or regulatory compliance. External dependencies are more unpredictable, since delays or changes may come from groups with different priorities. Recognizing whether a dependency is internal or external helps set realistic expectations. It also guides where to focus negotiation, alignment, or risk planning. By distinguishing between the two, teams can better anticipate delays and avoid treating all dependencies as equal.

Pro Tip: Separate internal from external dependencies to identify where you can act directly and where you must coordinate.

Dependencies vary in how strictly they shape the order of work. Mandatory dependencies represent conditions that must be met before another task can begin. For instance, a data pipeline must be established before analytics dashboards can display accurate information, or a user authentication system must be in place before sensitive account features are released. These are non-negotiable steps tied to logical or technical constraints.

Discretionary dependencies, on the other hand, are influenced by choice and best practice. A team might decide to refine onboarding flows before enhancing reporting, even though the reporting feature could technically be developed first. Similarly, designers may choose to polish a new settings page before adding shortcuts, not because it is required, but because it aligns with their workflow. Distinguishing between mandatory and discretionary dependencies gives teams flexibility. It ensures they do not overestimate risks for tasks that can be safely rearranged and keeps attention focused on the truly critical blockers.[3]

Pro Tip: Challenge discretionary dependencies to see if rearranging tasks could save time without harming outcomes.

Time-based dependencies describe how the start or finish of one task is linked to another. Here they are:

- Finish-to-start is the most common dependency type, where one activity must be completed before the next begins, such as finalizing UI designs before development starts.

- Start-to-start means tasks begin together, like running security tests at the same time as setting up monitoring systems.

- Finish-to-finish requires tasks to end together, for example completing both content writing and translation at the same time for a product launch.

- Start-to-finish is the least common dependency type, where one task cannot end until another has begun, like ensuring a new support shift has started before the previous one closes.

Visualizing these relationships helps teams anticipate where delays are most likely to spread. Tools such as dependency charts or workflow boards make these links visible, reducing the chance of overlooking them. Clear mapping also supports coordination, as it shows who depends on whom and when. By analyzing the timing between tasks, product managers can identify where flexibility exists and where precise sequencing is critical.

Pro Tip: Use visual maps to clarify how the timing of one task affects others across the project.

Dependencies rarely exist in isolation. They often form chains, where the delay of one step cascades into others. The longer and more complex the chain, the higher the risk. For example, if a third-party integration is late, it can hold back testing, documentation, and marketing, delaying an entire release. Recognizing fragile

Risk management begins by mapping out these chains and identifying points of failure. Product managers can add buffers, set parallel work streams, or plan alternatives when delays are likely. Communication is equally important. Teams and stakeholders should be informed which dependencies are critical and which delays can be absorbed without major disruption. By treating dependencies as potential risks rather than fixed facts, teams reduce surprises and can respond quickly when problems arise.

Trade-offs are complex because every option carries both advantages and drawbacks. Without evidence, decisions often lean on intuition or stakeholder pressure, which can create bias. Data provides a way to compare alternatives with more structure. Metrics and user research highlight which

At the same time, data is not a cure-all. A single number, like usage frequency or

The real value of data-driven decisions is not in eliminating trade-offs but in making them transparent and defensible. When product managers can show why one path was chosen and what was sacrificed, teams understand the reasoning and are more likely to align around it. This combination of evidence and clear communication turns constraints into informed choices rather than guesswork.

Pro Tip: Treat metrics as guides, not absolutes, by considering both their advantages and unintended effects.

Trade-offs and dependencies are not only delivery concerns but also drivers of long-term choices. At a strategic level, they help product managers decide where to invest first. For example, a team may delay launching a new feature in order to complete an API that multiple products will use. This creates a short-term trade-off but sets up faster progress later. Similarly, investing in core security updates before building new functionality ensures compliance and reduces risk across the portfolio.

Looking at dependencies across teams also prevents siloed planning. If

Pro Tip: Treat constraints as signals for where to focus effort and unlock broader impact.

References

Topics

From Course

Images provided by

Share

Similar lessons

What PMs Actually Do

The Art of Prioritization