How People Seek Information

Explore how people seek information and learn how to tailor search experiences to meet their needs

Not all information seeking is the same. Sometimes, users know exactly what they’re looking for. For example, if users need the schedule for a local fitness class, they can quickly retrieve it from the gym’s website by searching their timetable. Other times, users might have only a general idea of what they need. For instance, they may want to learn more about physical activities in their city without a specific end goal in mind, just exploring various tips and techniques.

These different approaches are called modes of information seeking. Sometimes, people search systematically, following a clear path to find specific information. Other times, they browse more casually, exploring and discovering information as they go, often digressing from their original task. Understanding these modes helps in designing better user experiences.

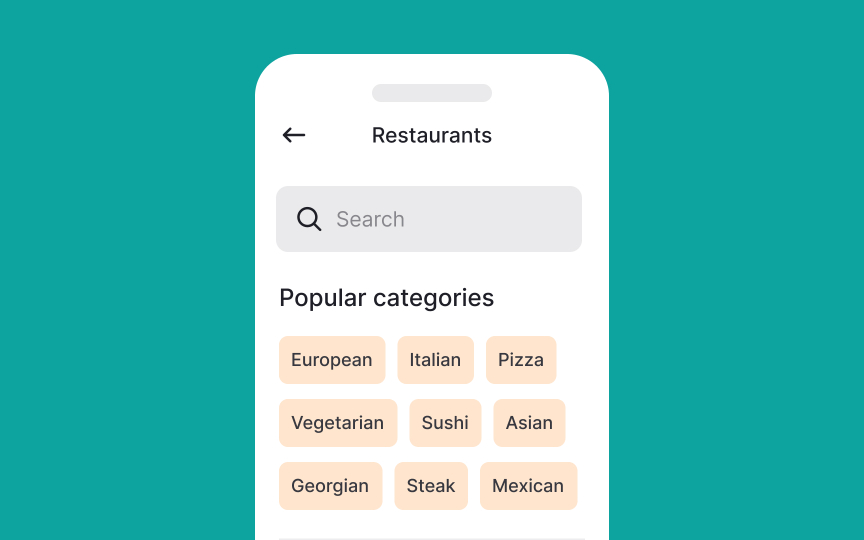

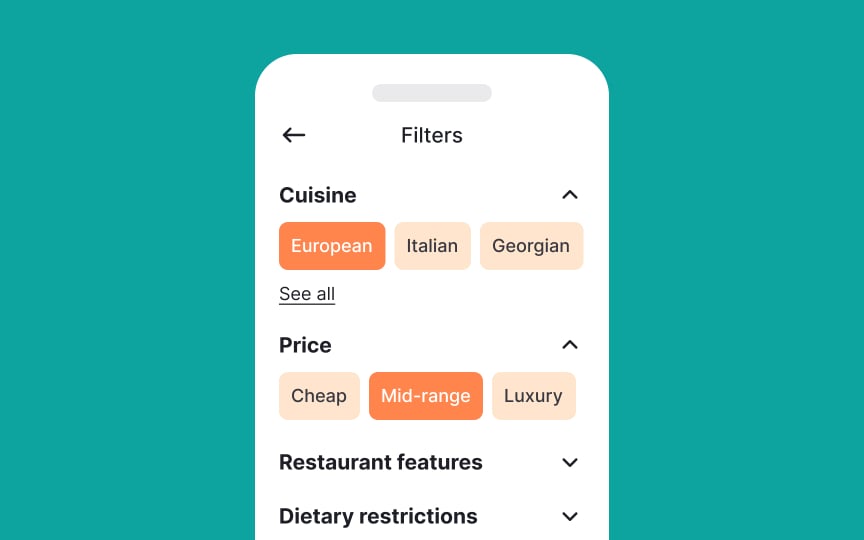

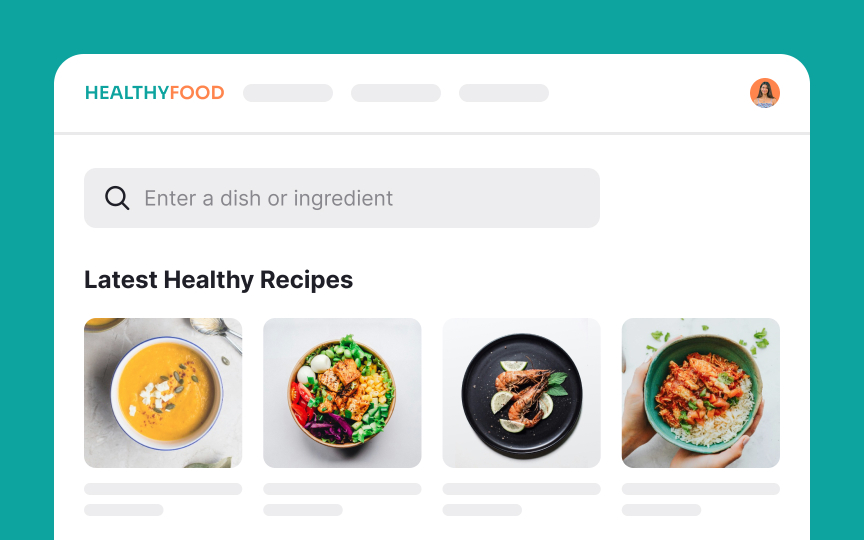

Directed browsing is a mode of seeking information where users have a specific goal in mind and navigate directly to find it. This approach is systematic and focused, much like scanning a list for a known item or verifying facts. For example, imagine you're planning a vacation and need to find a hotel. Instead of leisurely browsing through travel blogs and guides, you go directly to a travel booking site. Once there, you use filters to narrow down your

Directed browsing saves time and effort by allowing users to hone in on exactly what they need. This mode of information seeking is essential for tasks that require efficiency and precision, ensuring that users can quickly and easily find the specific information they're looking for.[1]

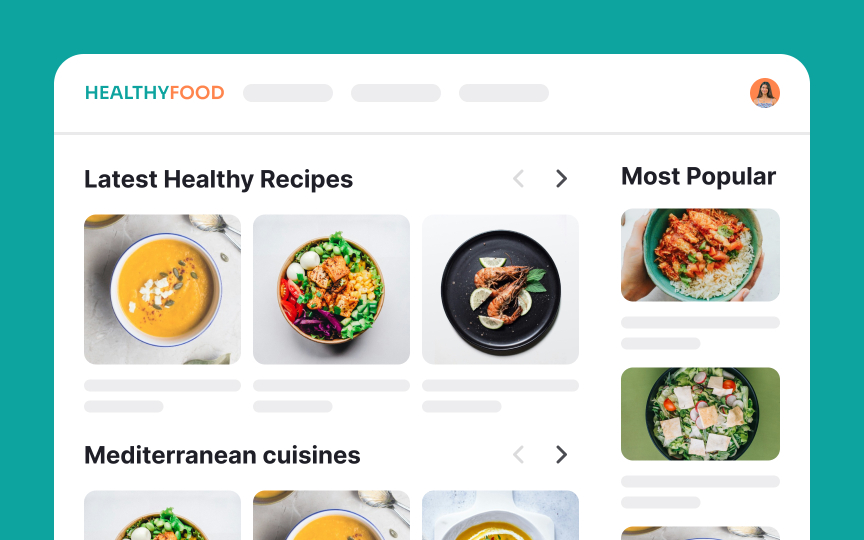

Semi-directed browsing is a mode of seeking information where users have a general idea of what they are looking for, but their goal is not fully defined. This approach is less systematic and more exploratory, often arising from a purposeful yet somewhat vague need. For example, imagine someone who wants to find a new productivity app but isn't sure what specific features they need. They might visit an app store and browse through various categories like task management, time tracking, and note-taking. They read user reviews, look at different app descriptions, and explore related apps. They aren't searching for a specific app — instead, they are exploring different options to get a sense of what might best meet their needs.

In semi-directed browsing, users benefit from a well-organized interface that offers multiple pathways to explore content, such as categorized sections, related articles, and

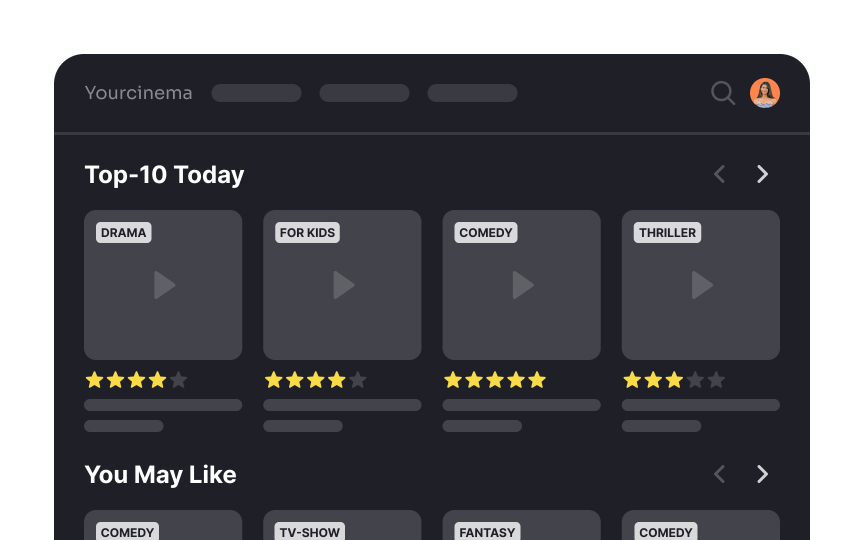

Undirected browsing is a mode of seeking information where users have no specific goal or focus. It's similar to flipping through a magazine or channel-surfing on TV. In this mode, users explore

Undirected browsing is driven by curiosity and the pleasure of discovering new, unexpected content. It's valuable for exposing users to a wide range of information and ideas they might not encounter through more targeted searches. Designing for undirected browsing means creating an engaging and diverse content environment that encourages exploration and delight.

Known-item

Known-item search is common in scenarios where users have clear, defined needs. It highlights the importance of having effective search functionality and intuitive navigation to help users locate their target quickly.

Exploratory seeking is a mode of seeking information where users have a general idea of what they need but can't clearly articulate it. Alternatively, the need may be so broad that users don't know where to start. This mode involves a lot of open-ended searching, with the goal often evolving as more information is discovered. For example, imagine someone planning a vacation without a specific destination in mind. They might start by browsing travel blogs, looking at different destinations, activities, and travel tips. As they explore, they discover new places and ideas, which gradually shape their vacation plans.

In exploratory seeking, users benefit from interfaces that offer diverse pathways to information, such as categorized

"Don’t know what you need to know" is a mode of seeking information where users are unaware of what information exists or what they truly need. In this scenario, users might think they need one thing but actually require something entirely different. For example, consider someone using a fitness app. They might

This mode of seeking is common when users are new to a topic or facing a complex problem. It highlights the importance of comprehensive and well-organized information that can guide users from their initial query to the deeper, more relevant information they didn't initially realize they needed. This includes offering suggestions for related

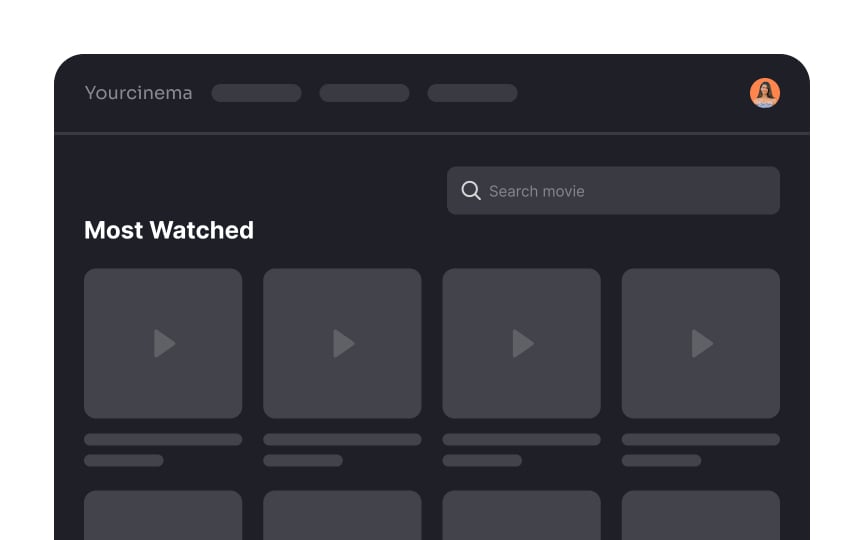

Re-finding is a mode of seeking information that involves looking for something users have already encountered. This often-overlooked mode is crucial for users who need to revisit information or resources they found valuable in the past but can't immediately recall where to find them. For example, imagine someone who read an insightful article about digital marketing strategies a few weeks ago. Now, they want to refer back to it for a project. They remember some keywords and the general topic but not the exact source. They might use their browser history, bookmarks, or

Re-finding highlights the importance of features like search history, bookmarks, and well-organized

As users browse and seek information online, their needs often evolve. Initially, users might have a specific question or goal, but as they explore, new information can reshape their understanding and objectives. This ongoing evaluation process means that online information seeking is more like a negotiation between the seeker and the system.

Designers need to account for this evolving nature of information seeking. Instead of assuming users will follow a single, direct path to their goal, create flexible

Also keep in mind the goal of optimizing users' time. Rather than presenting all navigation options at once, which can be overwhelming, prioritize the most important links and features based on primary user types and key tasks.

We are all creatures of habit, and this extends to our web browsing behavior. Users often rely on a limited number of pages within a site, frequently revisiting these familiar pages. This habit creates a hub-and-spoke style of

To support users' habit of revisiting pages:

- Ensure that key pages load quickly and are easily accessible.

- Implement features like a "Recently Viewed" or "Continue Shopping" section to help users quickly return to pages they have previously visited.

- Keep navigation paths short and minimize transient pages — those that serve no long-term purpose.

Users often browse quickly, spending only a few seconds on each

To accommodate this behavior:

- Create fast-loading pages with clear, concise, and immediately accessible information.

- Use visual hierarchies, bullet points, and bold headings to help users quickly find the information they need.

- Ensure essential

links and features are easy to locate.

References

- Designing Web Navigation | O’Reilly Online Learning

- Designing Web Navigation | O’Reilly Online Learning

Top contributors

Topics

From Course

Share

Similar lessons

Intro to Information Architecture

Intro to Search Functionality in UI