Dependencies, Constraints, and Assumptions

Anticipate what could delay, limit, or distort a product plan by identifying key dependencies, constraints, and assumptions early.

Even the most carefully written product specification can fall apart if it ignores what stands in its way. Dependencies, constraints, and assumptions form the invisible framework that shapes how a product comes to life.

Dependencies reveal what must happen before something else can begin, ensuring teams build in the right order. Constraints define what cannot be changed: resources, time, or regulations that set clear boundaries. Assumptions capture what is believed to be true but not yet proven, turning uncertainty into trackable risks. Together, they determine whether a plan is realistic or just hopeful. Mapping these factors protects timelines, clarifies ownership, and reduces surprises once development begins. Knowing how to spot and document them inside a product spec helps transform uncertainty into control and connects this lesson to every stage of specification writing, from defining features to managing scope and delivery.

Every product depends on a chain of actions where one step enables the next. These links between tasks are called dependencies, and they define how smoothly a project moves from idea to release. When not identified early, they become the silent cause of delays, rushed fixes, and unclear expectations.

Dependencies make teams think in sequence. Before development begins, designs must be approved. Before launch, documentation and support channels must be ready. Listing such relationships in the product specification turns vague coordination into a clear structure. It helps every contributor understand where their work fits and when to expect input from others.

By treating dependencies as part of planning rather than as problems discovered later, product managers reduce uncertainty and align schedules across teams. This transforms the specification from a static document into a living map of progress.[1]

Not all dependencies are within the same scope of control. Internal dependencies occur inside the product team, such as a feature awaiting interface design or testing following development. These can be managed through sprint planning, shared timelines, and coordination meetings.

External dependencies, on the other hand, rely on actors or conditions outside the team’s influence. A release may depend on legal approval, a third-party vendor delivering assets, or another team finalizing an API. Because they are harder to predict, external dependencies need contingency plans and proactive communication.

Including both types of dependencies in a product specification makes planning more realistic. It signals where flexibility is needed and where coordination with external partners should start early. This awareness prevents small delays from growing into major blockers.

Dependencies differ not only by who controls them but also by how tasks are related in time. Understanding these relationships helps product teams plan in a logical, predictable order rather than relying on intuition. When each dependency type is clear, scheduling conflicts can be reduced and collaboration becomes easier.

There are four main relationships between tasks:

- Finish-to-Start: one task must finish before another can begin, for instance, development completing before testing starts.

- Start-to-Start: both tasks can start once the first begins, such as content writing beginning after the first interface screens are designed.

- Finish-to-Finish: one task must finish before another can close, for example, localization ending only after copywriting is finalized.

- Start-to-Finish: one task cannot finish until another starts, such as a night support shift ending when the morning one begins.

Recognizing these types helps teams identify their critical path, the sequence of essential steps that defines the minimum time needed to deliver a product. Including this logic in the product specification ensures that dependencies are visible, timelines are realistic, and cross-team coordination becomes easier to track.

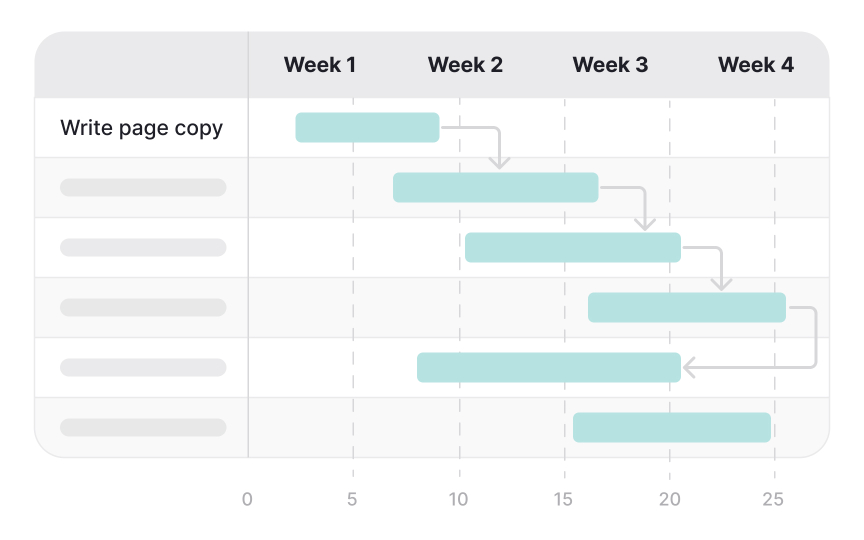

After identifying dependencies, the next step is to see how they connect. This is where dependency mapping becomes valuable. Tools like Gantt charts or network diagrams visualize the critical path, the sequence of tasks that determines when a project can finish.

Seeing these relationships helps teams focus on where a single delay can affect the overall outcome. For example, if user research is delayed, design and development both shift. Mapping such chains in the specification gives everyone visibility into where coordination matters most.

Managing dependencies well is not just about linking tasks but about communication. Reviewing these

Constraints define the boundaries within which a product can evolve. They are the conditions that limit time, resources, or possibilities. While dependencies describe how work connects, constraints describe what restricts progress. Recognizing them early helps prevent costly surprises and unrealistic planning.

Typical constraints in product development include limited budget, strict deadlines, legacy technology, and legal or compliance requirements. Each can directly affect the product roadmap. A short timeline can reduce testing coverage, while a fixed budget can limit the scope of features or markets. These factors often influence one another, which is why they are sometimes called the “project triangle” of time, cost, and scope.

Listing constraints in the specification helps everyone see the real limits the product operates within. It also creates transparency about trade-offs so that decisions are made consciously, not reactively.

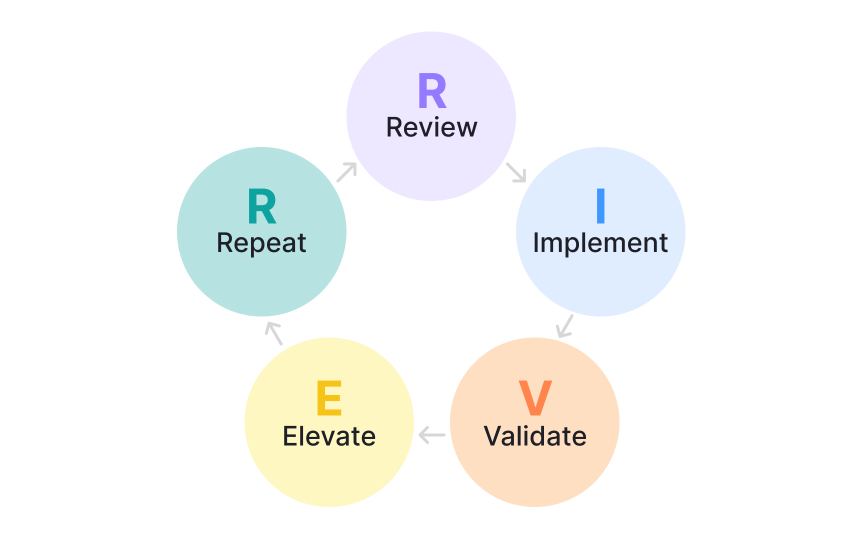

Managing constraints effectively means addressing them throughout the product lifecycle, not only during planning. The RIVER framework provides a structured way to do this through 5 repeating steps that help teams stay proactive and organized:

- Review compares current performance against product goals to identify where a constraint limits progress.

- Implement assigns ownership and defines how the team will act on those findings.

- Validate tracks whether the corrective steps are working, using measurable data such as cost, performance, or timing.

- Elevate comes into play when the team cannot resolve the issue alone and needs leadership support, extra resources, or a revised plan.

- Repeat ensures that this cycle continues regularly, preventing constraints from reappearing unnoticed later.

Documenting this process in the specification keeps constraint management visible and actionable. It turns a potential blocker into a continuous improvement loop that protects delivery quality and timing.[3]

Assumptions represent what the team believes to be true but cannot yet confirm. They often fill gaps during early planning when not all data is available. While assumptions can guide direction, leaving them untested creates hidden risks that may surface later in development.

Common examples include assuming that users will prefer one workflow over another or that a third-party integration will perform as expected. When such ideas are recorded in the specification, they should be phrased as testable statements rather than vague beliefs. For instance, instead of writing “users will find onboarding intuitive,” the assumption could read “80 percent of new users will complete onboarding within two minutes during usability testing.”

Documenting assumptions in this form allows them to be tracked and validated as part of ongoing research or technical proof. Once validated, they can move into confirmed requirements; if disproven, they help refine the product direction instead of undermining it later.

Pro Tip: Keep a small table in the specification with each assumption, its evidence source, and how it will be verified. This makes learning from validation results a routine part of the product process.

Dependencies, constraints, and assumptions rarely exist in isolation. Together, they form the system that defines whether a product specification remains realistic over time. A change in one often affects the others. For instance, a new dependency on an external vendor can introduce a timeline constraint, while an untested assumption may later challenge both cost and scope.

To manage this interconnection effectively, product managers can integrate DCA tracking directly into the specification. A simple structure can include a table listing dependencies with their owners, constraints with mitigation plans, and assumptions with validation status. Linking each item to related features or risks helps updates happen automatically when plans change. Regularly revisiting this section during team reviews ensures the document stays aligned with current priorities.

This approach turns the specification into a living reference rather than a static plan. It helps everyone see how each factor influences delivery and encourages more informed discussions around trade-offs and decisions.

Even when dependencies, constraints, and assumptions are well documented, their impact can shift over time. Small changes in context often signal deeper problems ahead. Learning to spot these warning signs in a specification helps teams react before issues turn into blockers.

Early signs might include vague ownership of critical dependencies, inconsistent timelines between teams, or assumptions that remain unverified after several sprints. Another indicator is a growing gap between planned and actual delivery dates, often revealing an overlooked external constraint. When such patterns appear, they should prompt a review of the DCA section of the specification rather than isolated troubleshooting.

Detecting these signals requires curiosity and regular attention. Specifications are not static but evolve as the product does. Reviewing them in sync with sprint retrospectives or roadmap updates ensures that potential risks are caught when they are still manageable.

References

Topics

From Course

Share

Similar lessons

Continuous Discovery Mindset

Business Outcomes vs. Product Outcomes