Ethics in Product Discovery & Definition

Learn the foundations of respect, inclusion, and genuine understanding through ethical research and problem framing

Product discovery determines what gets built and who benefits from it. Every decision about research methods, participant recruitment, and problem framing carries ethical weight. Teams hold significant power when they decide whose voices to include, what questions to ask, and how to interpret answers. These choices shape whether products serve diverse needs or reinforce existing inequities. How problems get framed determines which solutions emerge. Biased problem definitions lead to biased products, even with perfect execution. Responsible discovery requires continuously questioning assumptions, examining whose perspectives shape definitions, and ensuring the foundation for product decisions reflects genuine user needs rather than convenient narratives.

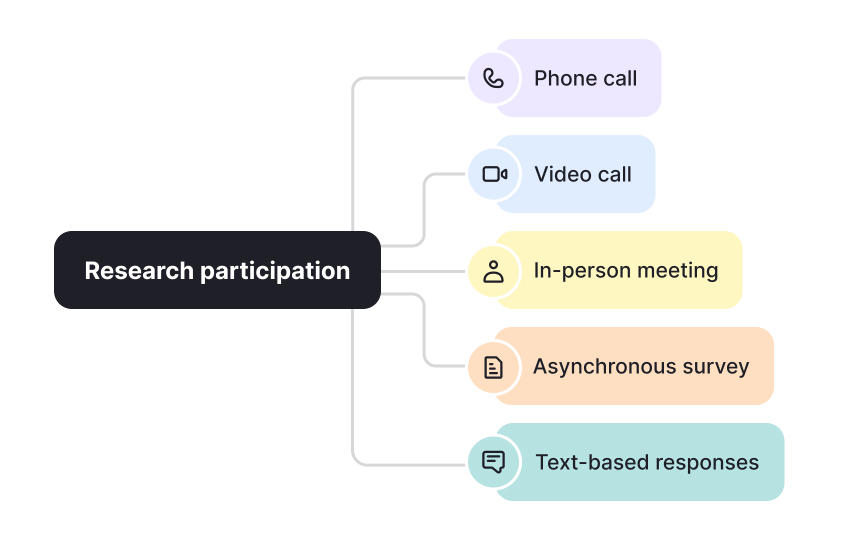

Inclusive research means offering multiple ways for people to participate. This might include phone calls for those without reliable video access, asynchronous options for different time zones, or shorter sessions for people with limited availability. Physical locations matter too. Choosing accessible venues, providing childcare support, or conducting research in community spaces rather than corporate offices removes barriers. Language accessibility extends beyond translation. Using plain language, avoiding jargon, and providing materials in multiple formats helps people with varying literacy levels and cognitive abilities participate fully. Audio, video, and text options let participants choose what works best for them.

Compensation also plays a role. Fair payment for participants' time shows respect and makes participation possible for people who can't afford to volunteer their expertise.

How teams find and invite

Ethical recruitment starts with honest communication about what participation involves. People deserve to know how much time they'll invest, what topics will be discussed, how their information will be used, and what compensation they'll receive. Misleading people about study length or purpose to boost participation rates is manipulative, even if unintentional.

Recruitment channels matter as much as messaging. Partnering with community organizations, posting in diverse online spaces, and using multiple languages expands who sees opportunities to participate. Screening criteria should be examined carefully. Requirements that seem neutral often have biased effects. For example, asking for corporate email addresses excludes freelancers and unemployed people. Requiring specific technology excludes lower-income participants.

How teams define problems determines which solutions get considered and whose needs get prioritized. Problem framing happens early in discovery, often before teams realize they're making consequential choices. Statements like "users need faster checkout" already contain assumptions about who users are, what they value, and what problems matter most. These frames can embed biases that persist through entire product cycles.

Teams naturally frame problems through their own experiences and perspectives. Product managers who commute by car might frame transportation problems differently than those who rely on public transit. Engineers comfortable with complex interfaces might underestimate

Biased problem framing often stems from whose pain points get labeled as problems worth solving. When teams only talk to power users, they frame problems around advanced features. When

Competitive analysis helps teams understand the market landscape, but the methods used to gather competitor information can cross ethical lines. Creating fake accounts to access competitor products, misrepresenting identity to speak with their customers, or using scrapers that violate terms of service all constitute deceptive practices. These tactics might yield insights, but they undermine trust and normalize dishonesty.

Plenty of legitimate ways exist to learn from competitors. Public information like app store reviews, published case studies, marketing materials, and features available to free users provide valuable insights without deception. Speaking with people who've used competitor products honestly, attending industry conferences, and analyzing publicly available data respects boundaries while still informing strategy.

The purpose of competitive analysis also matters ethically. Learning from others to improve your product differs from copying features to deliberately confuse users or studying competitors to identify exploitation opportunities. Responsible analysis focuses on understanding user needs competitors serve well or poorly, not on finding ways to unfairly undercut or mislead. Teams should question whether their competitive intelligence gathering would violate norms they'd want competitors to respect.

Informed consent means participants genuinely understand what they're agreeing to before

Consent isn't a one-time checkbox. Participants should feel empowered to withdraw at any point without penalty or awkwardness. This means explicitly telling people they can stop the session, skip questions, or ask for their data to be deleted. Recording adds another consent layer. Some people feel comfortable being quoted anonymously but not recorded. Others accept audio but not video. Offering granular choices respects different comfort levels.

Keep in mind that power dynamics affect consent quality. When research participants are employees, students, or otherwise in subordinate positions to researchers, their "yes" might reflect pressure rather than genuine willingness. Free participation doesn't mean ethical participation if people feel coerced. True consent requires removing pressure, providing clear opt-out paths, and ensuring no negative consequences follow refusal.

Cultural context shapes how people communicate, make decisions, and interact with technology.

Cultural sensitivity requires recognizing that Western product development norms aren't universal. Assumptions about privacy, family structure, communication styles, time management, and even color meanings vary across cultures. Teams can't simply translate interfaces or

Working across cultures means doing homework before research begins. Learning about communication norms, appropriate compensation, gender dynamics, and power structures helps teams avoid unintentional disrespect. Partnering with local researchers or cultural consultants provides crucial context that outside teams lack. Cultural sensitivity isn't about being perfectly correct, but about approaching unfamiliar contexts with humility, asking questions, and prioritizing learning over assumptions.

Vulnerable populations face increased risk of harm from

Extra safeguards become necessary when researching with vulnerable populations. This might mean obtaining guardian consent alongside participant assent, providing additional support during sessions, ensuring research locations feel safe, or working through trusted intermediary organizations. Compensation requires careful thought. Too little fails to value their time, too much might create coercive pressure to participate despite discomfort.

Power dynamics intensify with vulnerable populations. A person experiencing homelessness might fear refusing participation if they think it affects access to services. A child might not feel empowered to stop a session with an adult researcher. Teams must work harder to ensure consent is genuine, create comfortable environments for saying no, and question whether research truly serves these communities or merely extracts their stories.

Opportunity sizing estimates potential market value, but the methods used and populations counted reveal ethical priorities. Teams often size opportunities by counting only users they understand or markets they find attractive. This means underserved populations get labeled as "small opportunities" not because they lack needs, but because teams lack familiarity or perceive them as less profitable.

Ethical opportunity sizing questions whose needs count as valuable. When teams only measure markets with high purchasing power, they ignore people with genuine needs who could benefit from products. Sizing methods that only count current users of similar products miss people excluded from existing solutions. Focusing solely on markets with easy distribution channels overlooks populations facing access barriers.

How teams size opportunities signals what they value. Sizing based purely on revenue potential differs from considering social impact,

References

Top contributors

Topics

From Course

Share

Similar lessons

Understanding User Needs and Pain Points

User Research and Personas