Accessibility Research

Explore methods to gain a deeper understanding of all users to build accessible solutions

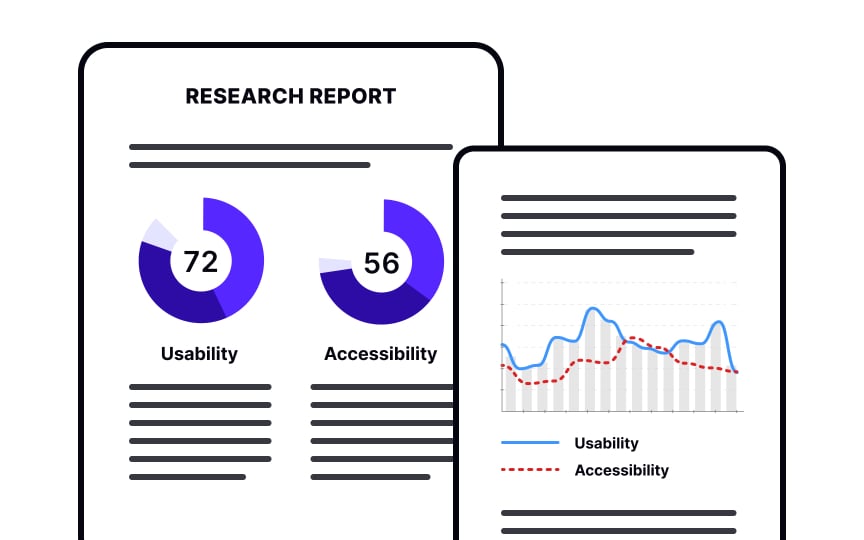

There is a significant overlap between usability and accessibility. Although accessibility primarily focuses on people with disabilities, research and design can elevate product experiences for all people.

Effective accessibility solutions must be based on deeper user understanding and validation through user research instead of just following guidelines and ticking boxes. To learn your users' needs, incorporate accessibility research into your standard UX practices.

There are many arguments for why you should include

Other benefits of conducting accessibility research include:

- Gathering data that represents your entire user population

- Identifying areas that interfere with any user’s ability to interact with a system

- Improving your product for all users and widening your user pool

- Discovering early on whether significant accessibility issues exist

- Connecting with people where they are and using their assistive tools and technologies in a realistic context

- Gaining critical insights that help you innovate on your products

- Positioning your brand as one with thoughtfulness towards everyone

When should you include users with

- Include some users with accessibility needs at every stage of the product development. This will ensure that people with disabilities drive your product’s innovation and accessibility.

- Use only participants with access needs at select stages of your research. For example, when you need to check your product for accessibility before shipping it.

Both approaches are suited to generative and evaluative research. Evaluate your project's needs and other constraints to decide what's most appropriate.[1]

Here are some changes you should consider implementing to ensure your

- Allocate extra time for accessibility research. You might need to give recruitment agencies more time to find the right participants, plan for longer research sessions, and spend more time analyzing your findings.

- Relax your participant criteria to prioritize access needs. For example, you might want to expand your demographic criteria to find participants with a wider range of disabilities.

- Adapt your test materials and protocols. Be prepared to provide alternative formats upon request: phone calls for screening, print and large print, plain-text email, sign language, etc.

- Budget for extra expenses. For example, recruitment agency fees for hard-to-find participants, travel costs, or lab licenses for assistive technology.

- Ensure accessibility in lab testing. This includes the physical accessibility of the lab and its access to assistive technologies.

- Make remote testing accessible. Ensure that the tools you use are accessible to participants. For example, the participants can log in, use screen sharing, adjust the sound, etc.

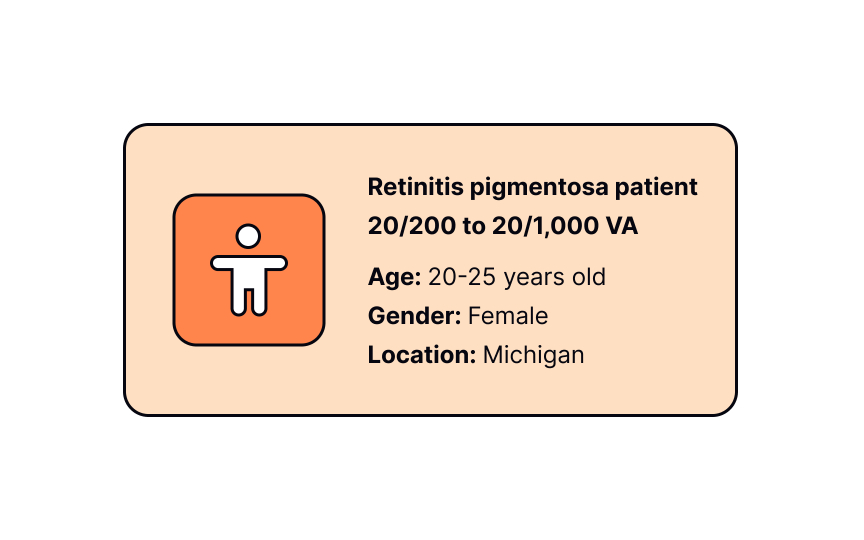

The more criteria you add to your recruitment screener, the longer it can take to find participants. To get enough people with

It’s common for people to have multiple impairments, and no person fits neatly into defined categories. Concentrate on people’s access needs rather than their specific disabilities. For example, cast your net for screen-reader users and magnification software users instead of visually impaired users. You can do this by asking participants about their assistive technology use. For example, “Do you use any assistive products to use computers on a daily basis?”

Depending on a person's disability, their

- People with different disabilities: Visual, physical, cognitive, auditory, and speech-related.

- People with varying degrees of impairment: For example, within visual impairments, look for participants who are color vision deficient, have low vision, or are blind.

- Users of different kinds and brands of assistive technology: For example, when recruiting screen reader users, look for people who use different brands like JAWs, NVDA, TalkBack, or VoiceOver.[2]

Before your sessions, ensure that you are familiar with disability etiquette. It will help you interact and communicate with participants respectfully and ensure that they feel relaxed and comfortable.

Basic disability etiquette includes:

- Avoiding victim language. For example, say "using a wheelchair" instead of "bound to a wheelchair."

- Not assuming their disability is a tragedy. Many people with disabilities are well adjusted to life and don't wish to be "fixed."

- Asking before making an accommodation or offering help. Doing so before asking can imply that the participant is incapable and come across as insulting.

- Making eye contact and speaking to your participant directly. Ignoring the participant by speaking to the interpreter or caregiver can feel like you don't see the participant as equal or capable.

- Letting participants speak and waiting until they finish before responding. Interruption can be especially disruptive for people with speech impairments and some cognitive disabilities.

- Familiarizing yourself with the etiquette specific to the person's disability or access needs. For example, if a participant has a guide dog, don't distract the dog from its job by petting or playing with it.[3]

Conducting

Consider ethical dilemmas of not providing accommodations or adjustments to the participant. You might find that spontaneous adjustments are necessary to assist participants with accessibility needs. Some participants might also need more facilitation adjustment than others. These adjustments won’t impact the accuracy of findings as the goal is to understand how participants' needs can be met, not to watch them struggle.

When reporting

How can you do this?

- Consider which issues affect everyone and which ones only affect people with disabilities. This categorization method won't always be clear, as some accessibility issues are also usability issues. To identify accessibility problems, look for those disproportionately affecting people with disabilities.

- Map the issues back to the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). The downside of this method is that the WCAG might not cover some issues clearly related to accessibility. Still, doing so can help you rate issues by severity and prioritize which ones to fix first.

To be able to ask participants about physical and mental attributes that relate to the

- Be clear about your objectives. Explain to participants from the start that you're focusing on

accessibility in your research. This will provide the context for your questions and let the participant decide if they want to take part in the study. - Check your local or federal laws. In some places, disability is considered medical information. It may not be considered ethical to ask directly about it, and even information that is volunteered may require special handling.

Remote

Here are some steps you can take to make sure your research runs smoothly:

- Make sure your preferred video conferencing tool is screen reader accessible. To better observe participants, you need them to be able to share their screen and computer audio.

- Call participants before the session to help them set up the tools you'll be using. This allows participants to feel mentally and physically prepared to join.

- Take advantage of the chat functionality. It can help communicate with participants with hearing impairments or even replace an interpreter.[4]

One of the ways to conduct research in person is by visiting participants at their homes, as it has several benefits:

- Participants will feel more relaxed in their own environment.

- Participants can use their own assistive technologies already set up for convenience.

- Researchers can get a better understanding of the real-world

accessibility requirements of participants.

Doing accessibility

Lab-based testing is one of the in-person

Here are some suggestions to ensure the highest possible standards for lab testing:

- Check if the lab has the assistive technologies your participants use. If that’s not possible, let participants know so that they may choose to bring their own devices.

- Provide easy-to-follow instructions from the building entrance to the lab and other facilities like waiting rooms or washrooms.

- Ensure that there are no trip hazards like wires, cables, or rugs on the floor.

- Inform the lab staff that you are conducting research and if they may need to provide additional support.

References

Top contributors

Topics

From Course

Share

Similar lessons

Intro to Accessibility

Inclusive Design Basics